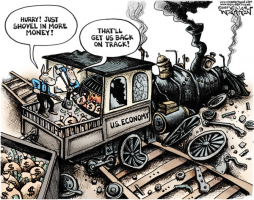

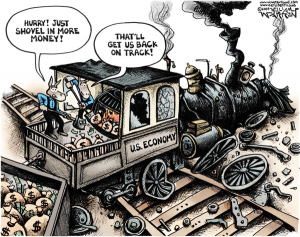

First quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is in, and well, the U.S. economy still stinks, growing at a paltry, inflation-adjusted rate of just 0.5 percent annualized.

First quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is in, and well, the U.S. economy still stinks, growing at a paltry, inflation-adjusted rate of just 0.5 percent annualized.

Unsurprisingly, the lack of growth falls well below the already dreary Federal Reserve expectations for 2016, which is projected in December 2.4 percent for the year. Which still stinks. Even as the economy struggles to catch up, perhaps we’ll even meet that growth projection this year. Which is the problem.

The U.S. economy has not grown above 4 percent since 2000, and not above 3 percent since 2005. While President Barack Obama goes around the world claiming he has been “Saving the world economy from a Great Depression” with his policies, in point of fact the last 10 years marks the worst performance of GDP since the 1930s. The rest of the world, particularly in emerging markets, have performed well above the U.S. in that timeframe.

And at the current slow-to-no-growth rates, the U.S. economy is poised to underperform its way into financial oblivion.

Without growth, the U.S. will be unable to meet its full faith and credit financial obligations both publicly and privately. Right now, the $19.2 trillion national debt stands at 105 percent of GDP.

The U.S. has sustained such largesse with extremely low interest rates, but that will only work for so long. Nominally, the national debt grew 5. 7 percent in the past 12 months. Compare that to 2015’s nominal economic growth — that is, before inflation adjustment — of 3.5 percent.

If those numbers held true for the foreseeable future, by 2050, the national debt would be $140 trillion, while the economy would be just $60.9 trillion — a whopping debt to GDP ratio of 229 percent. That is unsustainable, even with low interest rates.

Greatest default in human history?

And left unchecked, it may result in the greatest default in human history. Harvard economist Carmen Reinhart recently, remarkably called for debt restructuring — they dare not call it default but that is what restructuring is — writing for Project Syndicate, “[W]ith the largest economies, nearly eight years after the global financial crisis, burdened by high and rising levels of public and private debts, it is baffling that comprehensive restructuring does not figure prominently among the menu of policy options. Indeed, for the global economy, debt restructuring is the proverbial elephant in the room.”

But if the economy grows faster than the debt, the debt to GDP ratio shrinks — and there is no financial crisis. No need to restructure or default, or at least far less of a need. Reinhart does not see growth on the horizon, so she points to restructuring.

Without growth, the U.S. will be unable to maintain its global security posture, which the free world has depended on since the end of World War II to maintain freedom of the seas, operate the world’s nuclear defense deterrent and be able to respond to hotspots that threaten national and regional security.

With aging submarines, air force and missile defense and operations systems, the U.S. is unprepared for a major war — and that lack of readiness puts the lives of hundreds of millions of people at risk.

But with accelerated economic growth, revenue will be readily available to fashion a new fleet of 21st Century arsenals that will deter a major attack from other world powers. Defense hawks do not foresee growth and boosted revenue either, and so call for Congress with its scarce resources to prioritize spending towards the military.

Without growth, the U.S. will be unable to meet its commitments to Baby Boomers, 9 million of whom will be indigent and require Medicaid by 2030 for either nursing home or at-home care.

Overall public and private health systems will become overwhelmed as health expenditures could encompass 40 percent of GDP by 2080, as projected by Romneycare and Obamacare architect Jonathan Gruber of the Massachusetts Institute for Technology in 2011, writing for the National Bureau of Economic Research. Gruber wrote it was “doubtful” that the health care law alone would “fully solve the long run health care cost problem in the United States”. Gruber’s approach and the idea behind the law is to deal with the problem by controlling costs.

But the real solution again is to get the U.S. economy growing again — robustly — so that public and private systems are not so strained.

See a pattern? All of these questions are moot if the U.S. economy picks up the pace.

Some of the causes of the economic slowdown are easier to deal with than others. The demographic slowdown of fewer babies poses a generational challenge, with a lower relative growth of demand. As for the accumulation of too much debt public and private, which serves as a net drag on growth, that run-up of credit occurs very much as a function of growth being too slow. That is, we tend to borrow to move consumption to the present.

Other wounds are self-inflicted, such as $8.7 trillion of trade deficits since 2000 and the regulatory stranglehold particularly on energy production by the Environmental Protection Agency. Those could be undone or at least affected by a smart mix of policy that seeks to restore U.S. competitiveness globally.

Regardless of the causes — and there are many — everyone should agree that growth is the solution. Because the danger of no growth is default on our massive bond bubble, a crippled U.S. defense posture and seniors who will simply die waiting for care.

But if we just start growing — and fast — it all goes away.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.