A closer look at solar panels opens a wide array of questions that need answers.

A Popular Choice

Solar panels have been heralded as the alternative to fossil fuels for decades. Most readers have likely seen exciting headlines claiming we could power the world’s energy demands multiple times were we simply to cover the Sahara Desert with a solar farm the size of China. The fact that such endeavors would be unsustainable due to their size and the sheer amount of maintenance required or that the necessary infrastructure to bring this energy all around the world is simply unimaginable is irrelevant to those who dream of a solar future.

In the age of emissions trading and international climate conferences, nothing is applauded more than showing off some big investments in solar.

That’s fine; we’re all dreamers in one way or another. This fantasy has grasped many voters, however, and politicians are all too keen to jump on the gravy train of alternative energy. Solar panels are subsidized to an enormous extent, as are solar farms, be they public or private. In the age of emissions trading and international climate conferences, nothing is applauded more than showing off some big investments into harvesting the sun as an electricity supplier.

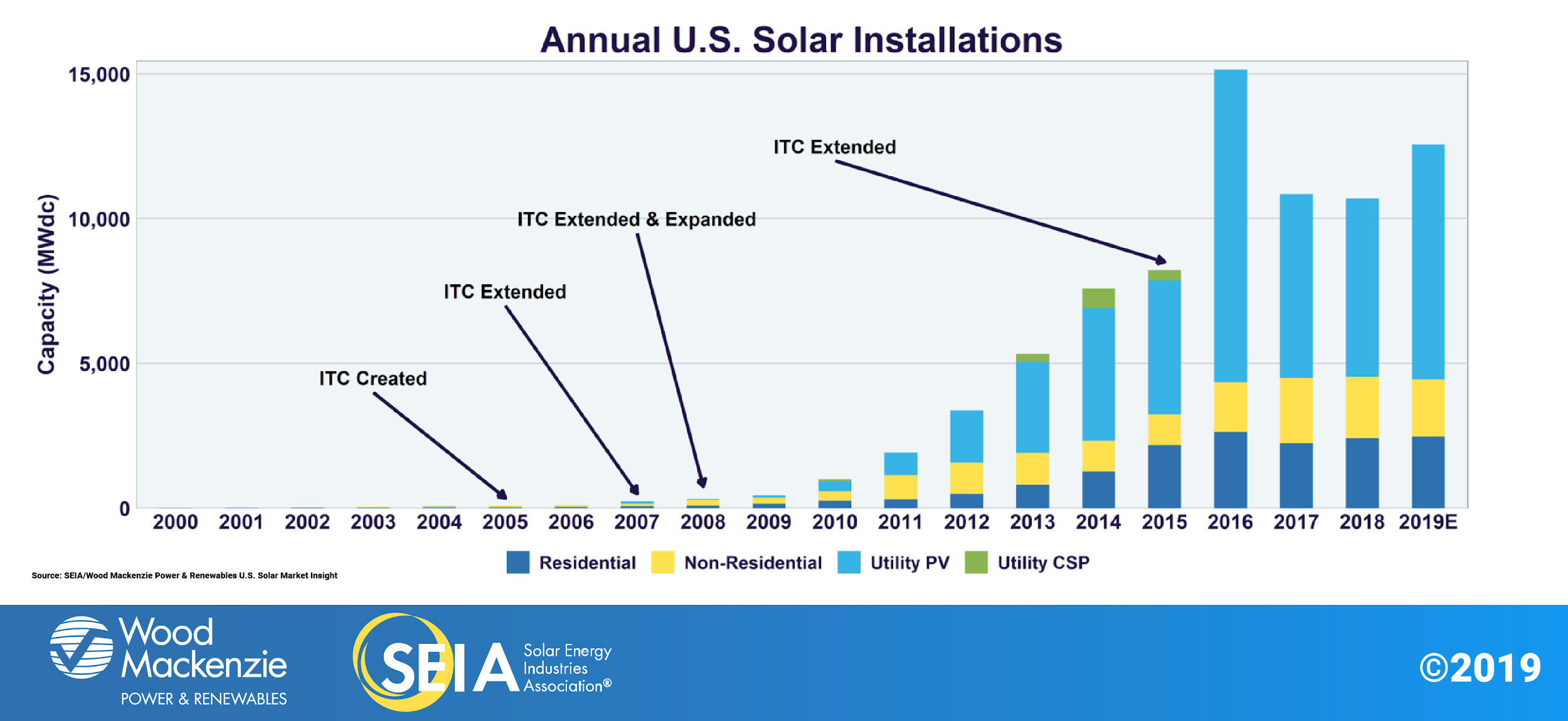

This zeitgeist is reflected in solar panel sales. The different arrows in the chart below point to the moments when Solar Investment Tax Credits (ITC) were introduced, extended, or expanded.

What’s Inside?

Beyond the clear misallocation of resources and energy market price distortions, there is a further environmental problem associated with solar panels.

Beyond the inefficient use of these resources to begin with (in the process of making crystalline silicon from silicon, as much as 80 percent of the raw silicon is lost), there are numerous human health concerns directly related to the manufacture and disposal of solar panels.

According to cancer biologist David H. Nguyen, PhD, toxic chemicals in solar panels include cadmium telluride, copper indium selenide, cadmium gallium (di)selenide, copper indium gallium (di)selenide, hexafluoroethane, lead, and polyvinyl fluoride. Silicon tetrachloride, a byproduct of producing crystalline silicon, is also highly toxic.

The pro-solar website EnergySage writes:

There are some chemicals used in the manufacturing process to prepare silicon and make the wafers for monocrystalline and polycrystalline panels. One of the most toxic chemicals created as a byproduct of this process is silicon tetrachloride. This chemical, if not handled and disposed of properly, can lead to burns on your skin, harmful air pollutants that increase lung disease, and if exposed to water can release hydrochloric acid, which is a corrosive substance bad for human and environmental health.

For any user of solar panels, this is not an immediate risk as it only affects manufacturers and recyclers. More disconcerting, however, is the environmental impact of these chemicals. Based on installed capacity and power-related weight, we can estimate that by 2016, photovoltaics had spread about 11,000 tons of lead and about 800 tons of cadmium. A hazard summary of cadmium compounds produced by the EPA points out that exposure to cadmium can lead to serious lung irritation and long-lasting impairment of pulmonary functions. Exposure to lead hardly needs further explanation.

Recycling Solar Panels

In one 2003 study, researchers drew attention to the fact that cadmium is the benefactor of special environmental treatment, which allows solar energy to be more economically efficient (as far as that word quite applies to solar energy even in the current state of subsidization). They wrote:

If they were classified as “hazardous” according to Federal or State criteria, then special requirements for material handling, disposal, record keeping, and reporting would escalate the cost of decommissioning.

This mirrors an answer given by Cara Libby, Senior Technical Leader of Solar Energy at the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), who admits that there is no lucrative amount of salvageable parts on any type of solar panel. She adds:

In Europe, we’ve seen that when it’s mandated, it gets done. Either it becomes economical or it gets mandated. But I’ve heard that it will have to be mandated because it won’t ever be economical.

It is no wonder that Chinese factories, when confronted with the exorbitant costs (both financial and environmental) of decomposing solar panel chemicals properly, prefer to release them into the environment rather than dispose of them in an environmentally safe manner.

Stanford Magazine also points out that solar energy has a higher carbon footprint than wind and nuclear energy. Ray Weiss, a professor of Geochemistry at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, explains that a number of solar panels release nitrogen trifluoride (NF3), a chemical compound 17,000 times worse for the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. As recently as 2015, he explained that many manufacturers were still struggling to figure out how to contain its release into the atmosphere.

Question the Narrative

Energy policy is not a place for emotion or action based on instinct. We throw around a lot of buzz words that lead us to the belief that one energy supply is “cleaner” than the other. The reality is that human action and interaction require a constant supply of energy. All forms of energy production have an impact on the environment.

Questioning certain narratives regarding the eco-friendliness of those classified as “renewable” but do not live up to an environmental standard that reasonable people could support is essential to both innovation and environmental protection.

Bill Wirtz Bill Wirtz is a Young Voices Advocate and a FEE Eugene S. Thorpe Fellow. His work has been featured in several outlets, including Newsweek, Rare, RealClear, CityAM, Le Monde and Le Figaro. He also works as a Policy Analyst for the Consumer Choice Center.

Learn more about him at his website.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.