The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office on Nov. 29 released an analysis describing its “current view of the economy in 2023 and 2024 and the budgetary implications.”

In short, everything looks bleaker than it did a little more than six months ago, when the CBO published its Budget and Economic Outlook report in May.

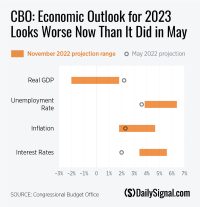

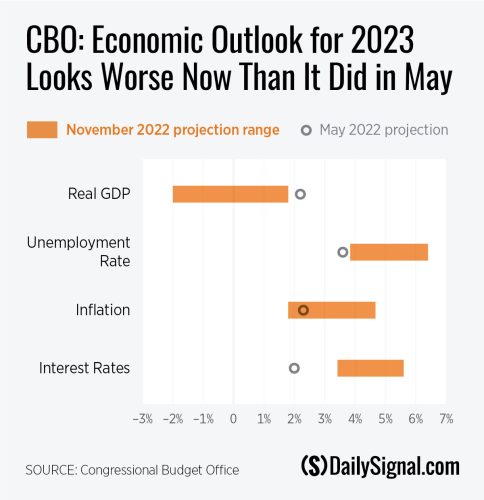

In the May report, the CBO projected that economic output would grow by 2.2% in 2023. The newest CBO update suggests there’s only a 1-in-6 chance that the economy will grow by more than 1.8%, and it’s as likely as not that the economy will shrink in 2023.

The CBO now expects the 2023 unemployment rate to rise. The report suggests joblessness will jump to between 3.8% and 6.4%, implying anywhere from a couple of hundred thousand to about 4.5 million more Americans will be unemployed next year than today.

How about inflation? The inflation picture is also less optimistic.

The CBO had previously projected that inflation would fall to near the Federal Reserve’s 2% target by 2023. Now, the budget office is not so sure. The latest CBO report pegs the most likely range for 2023 inflation at between 1.8% and 4.6%.

In other words, inflation will probably be lower than it was in 2021 or 2022, but will probably be worse than any other year in the past one to three decades.

And because inflation has proven to be a more persistent problem than many economists expected, the Federal Reserve has responded with greater increases in interest rates than the CBO had previously expected.

The CBO now expects three-month Treasury bills to pay between 3.4% and 5.6% interest rates in 2023, way up from the 2% it projected in May 2023.

That has huge implications for the national debt.

The CBO now estimates that the deficit in 2023 will be between 20% and 30% higher than it had projected in the May forecast, solely because of the revised estimates to gross domestic product, unemployment, inflation, and interest rates. That’s not even factoring in new legislation that ballooned the deficit since the last forecast.

The CBO noted that higher-than-expected interest costs were the primary reason for the dramatic uptick in deficit expectations. This should raise serious red flags for federal lawmakers.

When just a few months of higher-than-expected interest rates are the driving factor behind a $200 billion to $300 billion upward revision in the next year’s deficit, it demonstrates how dependent the federal government is on low interest rates to keep the debt and deficits even remotely under control.

Interest rates have been historically low—near zero—for almost 15 years. But with the recent outbreak of inflation, the Federal Reserve has tightened monetary policy, and interest rates have been on the rise.

For a country with $31.3 trillion of debt—more than a quarter-million dollars per U.S. household—rising interest rates are worrisome, to say the least.

Higher interest rates drive up the cost of servicing the already high national debt, leading to higher deficits each year. The faster growing debt then forces the government to make interest payments on an even larger amount. All of this makes investors wary of holding U.S. securities, so they in turn demand higher interest rates.

It’s not hard to see how this vicious cycle could snowball out of control if lawmakers and federal officials aren’t careful.

The overly optimistic May outlook forecast that the federal debt would rise from 100% of GDP in 2021 to 185% of GDP by 2052. The November update shows that matters are even worse than that.

For context, leading up to its debt crisis in 2008, Greece had a debt-to-GDP ratio of about 127%.

Greece’s debt crisis should serve as a cautionary tale for U.S. lawmakers that it’s time for America to get our spending and debt problem under control while we still can.

The European Union and the International Monetary Fund stepped in during Greece’s debt crisis to bail out the government and stave off default, but the Greek economy was still left in shambles.

During the height of its debt crisis, Greece had an unemployment rate of nearly 30%. Greece’s economy today is still almost 30% smaller today than it was in 2007. The Greek downturn has been even more severe and long-lasting than America’s Great Depression.

Is a similar disastrous scenario inevitable for America? No, but debt isn’t free, and Americans will pay for it one way or another.

And like a homeowner neglecting a crumbling foundation, a disaster is considerably more likely if Washington chooses to ignore America’s growing spending and fiscal problems.

Yet, that’s precisely what Congress seems inclined to do, and it’s not just one party that wants to whistle past the graveyard.

During the lame-duck period before the newly elected Republican majority takes control of the House, some Republicans have signaled their willingness to work with outgoing Democrats to pass yet another massive omnibusspending bill.

House Republicans also voted down a ban on budget earmarks—the favorite tool of members of Congress for bringing pet projects home to their districts.

None of this bodes well for Americans who were optimistic that divided government would stop America’s march to fiscal ruin.

Preston Brashers is a senior policy analyst focusing on tax policy at The Heritage Foundation. Reproduced with permission. Original here.