The Summit of the Future in 2024 is an opportunity to agree on multilateral solutions for a better tomorrow, strengthening global governance for both present and future generations

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres

A U.N. policy brief has revealed that the United Nations is seeking vast new powers and stronger “global governance” tools to deal with international emergencies such as pandemics and economic crises. The plan to create an “Emergency Platform” has already drawn strong concern and criticism from U.S. policymakers and analysts, who have expressed concern about the U.N.’s well-documented corruption problems and its track record of dealing with previous emergencies.

Former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for International Organizations Kevin Moley has criticized the proposal, stating that “allowing the U.N. to deal with this is the equivalent of putting the CCP in charge of global emergencies.”

Despite this, the Biden administration appears to support the plan, and U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres has called for “strengthening global governance” for current and future generations. However, exactly what would constitute an emergency that would trigger the U.N. emergency response remains unclear.

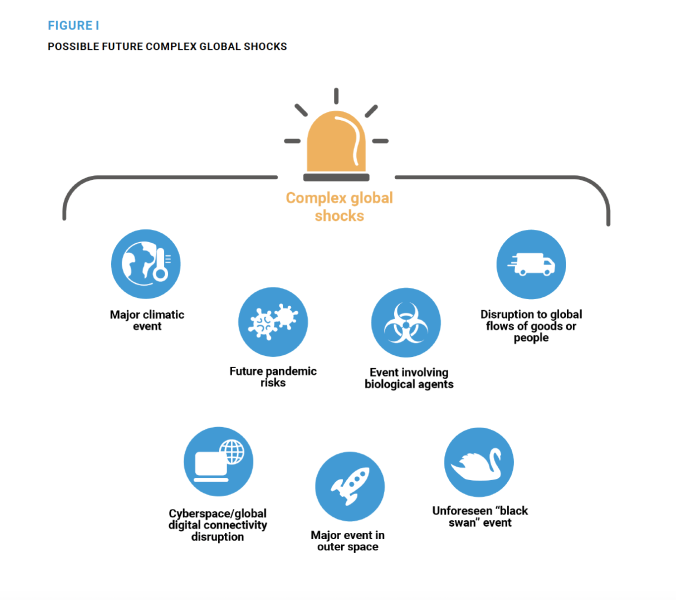

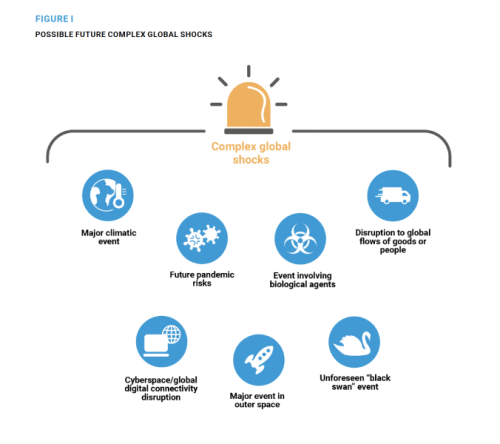

Despite claiming to only intervene in crises with global consequences, the U.N.’s emergency protocols may still be triggered by crises that don’t meet this standard. The policy brief’s broad categories of emergencies that might activate the protocols are vague, and the U.N. frequently cites the COVID-19 pandemic as a justification for these expanded powers. The U.N. chief’s socialist background is also concerning, as is the emphasis on strengthening the World Health Organization, an organization that has faced criticism for its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of clarity and transparency in this proposal is deeply worrying, and U.S. policymakers and analysts are right to express concern.

The U.N.’s emergency protocols would convene government leaders, U.N. agencies, international financial institutions, the private sector, civil society, and experts to respond to crises, with the U.N. secretary-general in charge of identifying participants and overseeing their contributions. These contributions could range from financial support to policy changes.

The urgency of this proposal is linked to concerns that international emergencies could hinder progress towards the Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, a controversial initiative that covers most areas of life and has faced massive criticism from skeptics as it is designed to force us to eat bugs and plants, live in densely populated cities, abandon the countryside to “rewilding”, end travel for regular people, redistribute wealth to low-income countries, and other totalitarian acts which suppress the populace under global elites. The U.N. and the Obama administration strongly supported these goals, as did the CCP.

Despite the U.S. Senate not ratifying the global agreement as required for all treaties, policies in business and government are being aligned with the Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. The U.N.’s emergency-response plan is aimed at mitigating the impacts of complex global shocks on these goals, and is part of a wider effort to strengthen “global governance” and establish a renewed “social contract” that aligns with the “Great Reset” announced by U.N. officials and Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum.

Critics are also very concerned about the influence of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) within the U.N., which has been felt during the pandemic and could be even more dangerous during future global emergencies.

Former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for International Organizations Kevin Moley rejects the U.N. plan, pointing out the CCP’s control over key U.N. agencies and member states. Moley warns that approving the emergencies protocol plan would effectively put the communist regime in charge of global crises and is a “recipe for disaster.” He believes that the U.S. State Department needs to be more skeptical of U.N. proposals and prioritize American sovereignty over global governance. The lack of transparency, accountability, and protection of American interests in this proposal is deeply concerning, and U.S. policymakers and analysts should continue to scrutinize it with caution.

Moley is critical of the U.N.’s plan, instead calling for a complete overhaul of the U.S. State Department, which he believes was obstructed by career bureaucrats throughout Trump’s tenure. Moley asserts that the State Department does not represent American interests, but rather serves the agendas of billionaire financier George Soros, his Open Society foundations, and globalism, undermining American sovereignty.

Another critic, former U.N. internal investigator-turned-whistleblower Peter Gallo, highlights the U.N.’s history of corruption, politicization, and scandal, including cases of humanitarian aid being weaponized for political purposes.

Even more disturbingly, Gallo points to the sexual exploitation and trafficking of victims during disasters by U.N. personnel, with more than 60,000 women and children estimated to have been raped and sexually abused during the previous secretary-general’s tenure alone. Gallo criticizes the lack of accountability for these atrocities and attacks on U.N. whistleblowers who have tried to stop it.

Overall, the U.N.’s proposal is rife with concerns regarding transparency, corruption, and sexual exploitation, and critics like Moley and Gallo raise valid points about the potential dangers of implementing such a plan.