Incentives matter, and when you change incentives, you change behavior.

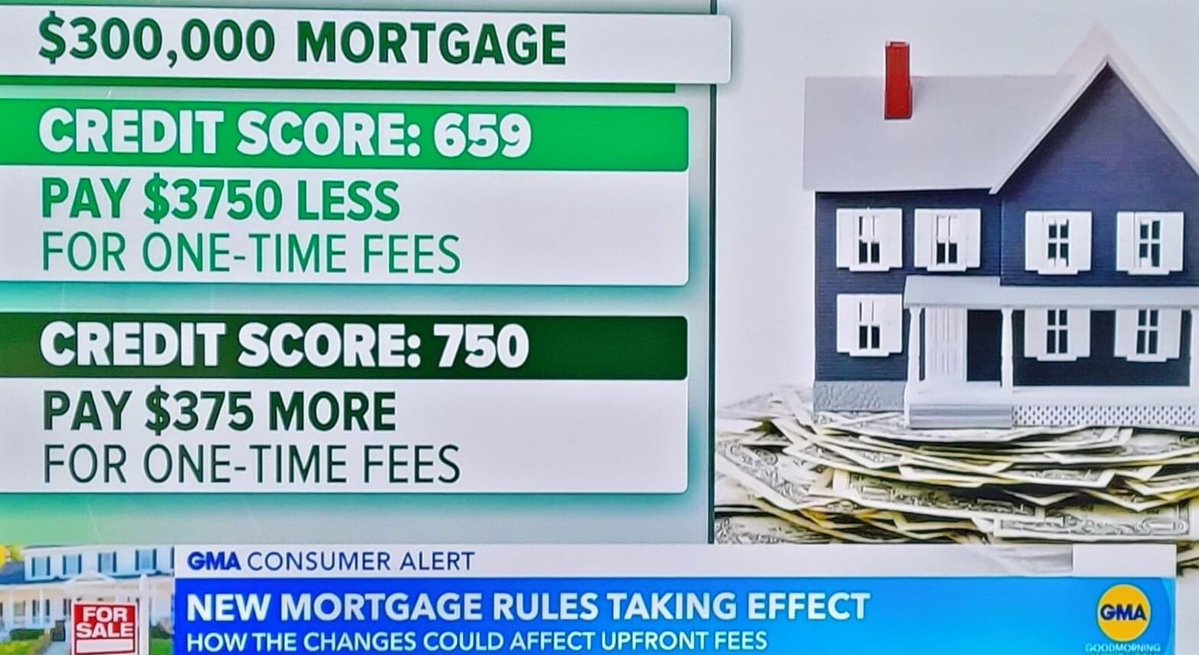

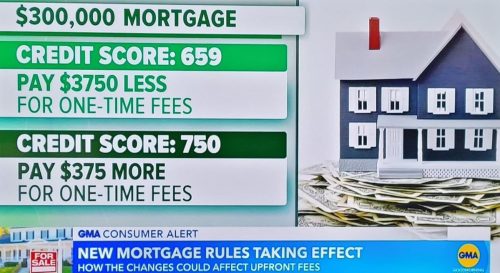

The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) has begun to implement new rules for mortgage borrowers. The result of these new rules is that, everything else held constant, some borrowers with relatively higher credit ratings who make larger down payments on houses will pay higher fees than they did before. Likewise, some borrowers with worse credit ratings who make smaller down payments will pay less.

I’m being very careful with my words above for a reason. Put bluntly, pedantic fact-checkers are trying to lie about this policy. Consider the example below from Snopes:

- “Some people with higher credit scores will pay more in fees than those in similar situations under the old rule.”

- “Conversely, people with lower credit scores will pay less.”

- “And even those with higher credit scores will pay less once the new plan takes effect.”

These statements all occur one right after another in the Snopes “fact-check”.

Statement 2 is straightforward. People with worse credit will pay less. But look at statements 1 and 3. With this policy, some people with higher credit scores will pay more, but even those with higher credit scores will pay less. How can we make sense of this blatant contradiction?

The answer is that Snopes is saying that some people with higher credit scores will pay lower fees in certain situations under the new rules. But the fact that some people with higher scores will pay lower fees does not mean all people with higher scores will pay lower fees.

As Snopes points out, this policy does have winners and losers. Take their own example.

“Borrowers in the credit score range of 720-739 who plan to make a down payment of 20% on the home value would see a fee increase from 0.750% (under the old structure) to 1.250% (under the new plan effective starting May 1, 2023). So, a borrower in that credit score range making a down payment of $80,000 (20%) on a home value of $400,000 would now have to pay an upfront fee of $4,000 (1.25%) on the loan of $320,000 (80%). Under the old plan, that fee would have been $2,400 (0.75%).”

So the fee is higher than it used to be for a certain set of responsible borrowers putting 20% down! Snopes follows up by giving an example of how a different high credit score borrower in a different situation will have a lower payment. But the fact that some high credit borrowers will benefit doesn’t change the fact that the losers of the rule change tend to be those with high credit who make large down payments.

If the government announced 10% higher income taxes on every woman in the country except Jill Biden, would it be wrong to say the tax punishes women because one woman is exempt? Of course not. Fact-checking pedantry uses the exception to ignore the rule.

Snopes Ignores How We Typically Talk About Accountability in Politics

Another weird thing Snopes does in the opinion piece—I can’t call it a “fact-check”—is try to claim the Biden administration is unaccountable for the change. Interesting logic: it isn’t that bad, but if it is that bad, it isn’t Joe Biden’s fault!

Snopes claims separation from Biden and the policy by invoking the FHFA’s status as an “independent regulatory agency.” Like many Federal agencies, there is a degree of separation between the sitting president and the FHFA. The EPA, FCC, SBA, CIA, and over a dozen other agencies fall into the classification of independent regulatory agencies.

The problem is, these agencies aren’t purely independent from the executive, and it would be silly to claim otherwise. To start, the current head of the FHFA, Sandra Thompson, was nominated by Joe Biden. This information alone seems enough to merit responsibility on the Biden administration for FHFA rule changes.

The other issue is this standard doesn’t seem to be applied consistently. If Trump’s EPA nominee rolled back environmental protections, and those changes resulted in environmental disaster, do we expect Trump wouldn’t be blamed? Executives are consistently held responsible for the agencies whose leaders they choose.

Snopes Misunderstands Economic Logic

Snopes also quotes FHFA director, Sandra Thompson, to address “misconceptions”. The issue with these statements is they betray a lack of understanding of the relevant margin of analysis.

First, Thompson is quoted as saying, “higher-credit-score borrowers are not being charged more so that lower-credit-score borrowers can pay less. The updated fees, as was true of the prior fees, generally increase as credit scores decrease for any given level of down payment.”

The problem is that the second sentence here is completely irrelevant to the first. No one is claiming that the updated fee schedule gives those with lower credit better rates than those with high credit. The (true) claim is this policy gives those with lower credit scores better rates than before the policy, while giving some with better credit scores worse rates than they had before the policy.

Consider an example. Imagine there are two people—a rich person and a poor person. The rich person is taxed at $100 per year and the poor person is taxed at $5 per year. Next year a new tax policy is passed and the poor person is now taxed at $6 and the rich person is taxed at $99.

Clearly the effect of this policy is to benefit the rich person relative to the poor person. The poor person is still taxed less than the rich person (just like those with higher credit scores still get lower overall rates), but the effect of the policy change was to increase taxes on the poor (just like the FHFA policy is increasing rates on some high credit borrowers relative to low credit borrowers).

Again, this policy also tends to penalize those who make down payments of 20% or more. Some have rightly pointed out this will incentivize people to lower their down payment. In an effort to debunk this obvious reality, Thompson, and Snopes in quoting her, make an error which leads to faulty analysis.

Thompson says, “the new framework does not provide incentives for a borrower to make a lower down payment to benefit from lower fees. Borrowers making a down payment smaller than 20 percent of the home’s value typically pay mortgage insurance premiums, so these must be added to the fees charged by the Enterprises when considering a borrower’s total costs.”

So here’s Thompson’s logic. When your down payment is less than 20% of the purchase price, you are required by the bank to purchase mortgage insurance. The cost of mortgage insurance tends to be greater than the fee reduction for borrowers with lower down payments, so there is no perverse incentive. The problem is Thompson ignores a crucial feature—people like to have money on hand.

Consider an example. Imagine a buyer purchasing a $200,000 house. Let’s say a 20% down ( payment ($40,000) leads to a monthly payment of around $1400. Now let’s say a lower payment of 10% leads to a payment of around $1700 with $100 of that increase being due to required mortgage insurance.

If a person has 20% down, they’ll definitely put 20% down for the lower payment, right? Wrong. While this may generally be true, some people might value having an extra 10% ($20,000) on hand more than they value a lower payment. And, if someone is on the borderline choosing between a higher monthly payment and more cash on hand, the new policy lowering that monthly payment for those with less than 20% may push someone to choose a lower down payment with more cash on hand.

If You Subsidize Something You Get More of It

Despite Thompson’s claim that the relatively higher fees for those with better credit are not meant to subsidize the lower fees for those with worse credit, this is hard to believe. Again, Thompson’s justification that those with lower scores still pay higher rates overall amount to a non sequitur when it comes to analyzing the change of this policy.

As is often the case in government accounting, there are plenty of ways to pretend this isn’t a subsidy. Revenue is up in one place and down in another, and all we have to do is pretend like these things are unrelated. See? No subsidy!

The effect of this policy, however, is that, relative to the old fee structure, there is more reward for having low credit and less reward for having certain levels of higher credit. Again, the only way this wouldn’t be true would be if rates were going down for all borrowers in equal proportion. But they aren’t. Some higher credit score individuals will pay more. In response, we should expect to see less effort in pursuing higher credit scores.

Incentives matter, and when you change incentives, you change behavior. No fact check pedantry will change this fundamental truth.

Peter Jacobsen

Peter Jacobsen teaches economics and holds the position of Gwartney Professor of Economics. He received his graduate education at George Mason University.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.