This week for Ask an Economist, I have a question from a reader named Mark. He says,

“I’ve worked with immigrants that recently moved to the US, and workers still living in their native country and working for me remotely.

My experience is that they’re on average, much harder working and more skilled (even in technical fields) than my American colleagues. The foreigners work hard, making no excuses, grateful for the work, and take every opportunity to better themselves. Americans, on the other hand, demand much higher wages, complain about the work, and make little effort to improve themselves.

Since the people from many of these poor countries are better workers, why are their home countries so poor? Immigrants on average start more businesses and do better in the US than US born citizens. With all their skills and ambition, it seems their home countries ought to be significantly richer than the US cities, yet this isn’t the case. What’s the cause of these countries’ poverty?”

Mark asks perhaps the single-most important question in the history of economic thinking. Why do some countries grow rich while others stay poor?

A Long History of Answers

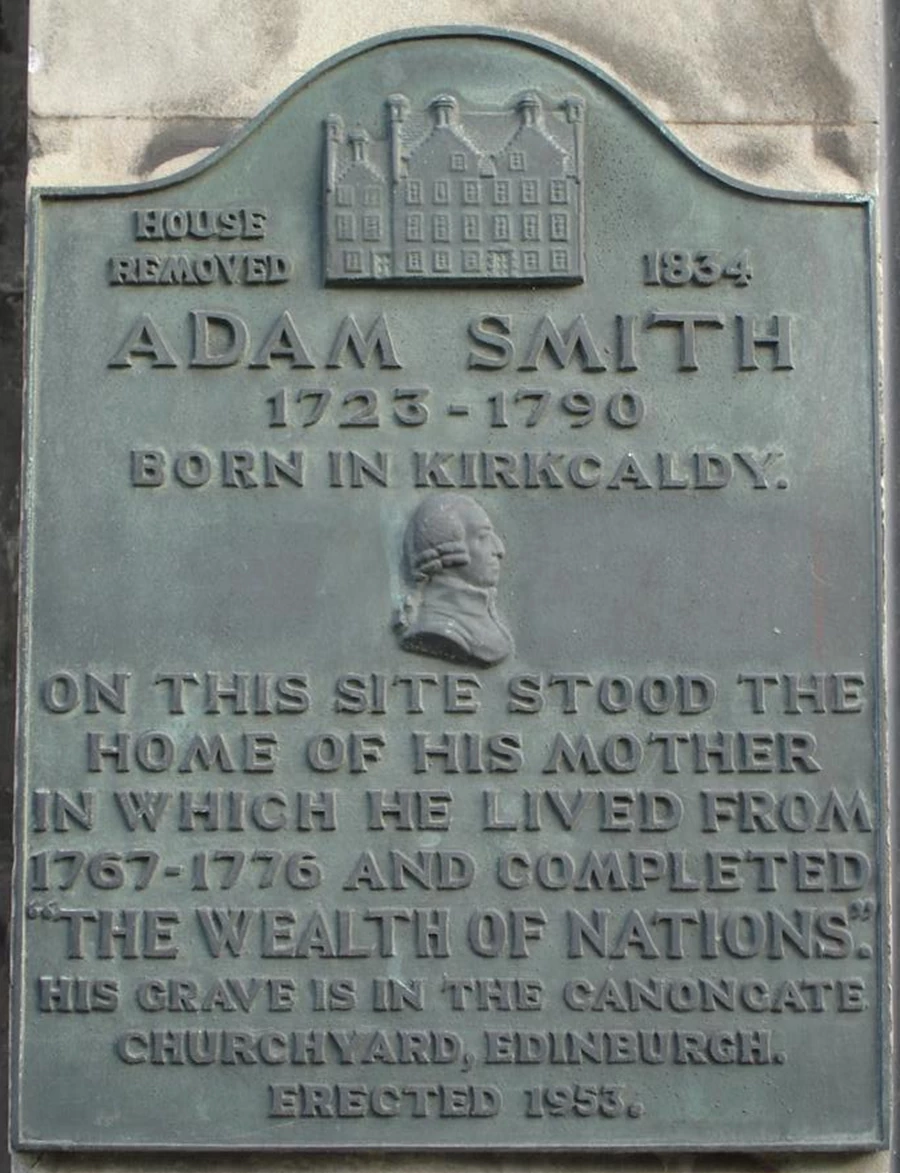

In 1776, Scottish philosopher Adam Smith published perhaps the most influential work in the history of political economy: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

This book, usually referred to as “The Wealth of Nations,” tries to answer the question Mark poses. Since then, wealthy countries have grown much wealthier, some poor countries have grown wealthier, but there are a substantial number of countries lagging behind.

Before we get into the right answer, we should spend some time talking about some popular wrong answers.

Economist Bill Easterly has done a great job chronicling some of these wrong answers in his book The Elusive Quest for Growth.

Easterly’s point in the book is simple. Throughout the late 20th century and into the 21st century, the United States and other countries have attempted to trigger economic growth in poor countries. These attempts have failed.

Easterly discusses three failed panaceas which experts believed would trigger development: investment, population control, and education. Before looking at each once, though, consider the unifying theme here. Developed countries tend to have higher levels of investment, lower birth rates, and more education. From this, experts have tried to infer that if these conditions are replicated in poorer countries, then development will follow.

This strategy has failed. It turns out these factors are more a consequence of growth than a cause. Let’s look at each failed panacea.

1. Investment

In the 1950s, experts began to believe that simply having machines and financial capital to take on big projects would make countries rich. This belief, ironically, was based on the (false) success of the Soviet Union. Soviet production numbers were going through the roof, and for decades economists believed they would overtake the US. Why?

The Soviet Union was industrializing through forced savings. By reallocating private resources to large industrial investments, it appeared the USSR was able to shock the economy into early industrialization. It turns out that this growth was illusory, as economist Murray Rothbard rightly predicted, leading to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

But the Soviet Union fooled many economists in the 1950s, so the model of centrally planned growth via investment took off. The belief was that because poor countries were in such dire situations, citizens had no ability to save. Without saving there is no growth. A vicious cycle was preventing growth.

So developing countries could fix this by giving the required investment for countries to have sustained growth. This investment would increase incomes, which would increase savings, and spur on permanent natural growth. Easterly calls this the financing gap approach.

The approach failed, though. Models failed to live up to their predictions, and poor countries were not made rich via air-dropped investments. The reason for the failure is the same reason noted by Rothbard in his analysis of the Soviet economy. Production is a means to the ends of consumption. If your production is not linked meaningfully to the well-being of consumers via the knowledge of prices, profit, and loss, then it will not lead to any sustained growth.

Central planners attempted to create production for its own sake, leading to the misallocation of capital and natural resources. Investment alone is not enough—you must have the right investments.

2. Education

A natural next plan for development experts was education. If increasing production via physical capital was not enough, maybe increasing knowledge or human capital would do the trick. Easterly chronicles how education development policy dominated from the 1960s to the 1990s.

The results did not bear out on this either. Easterly chronicles how study after study finds little to no correlation between education and economic growth. One study shows that as the education explosion happened in poor countries, the growth rate of income in these countries actually fell. This is exactly the opposite of what we’d expect if education theories were true. Another study found that for countries that grow 1% faster than average, education could only explain 0.06% of that in terms of growth in human capital.

Easterly points to several other types of studies which show a simple, consistent result: education does not create economic growth.

3. Population policies

Perhaps the worst theory to be tested in the developing world was the neo-Malthusian idea that large populations were the cause of poverty. Again, these theories were based on the unrigorous approach of simply trying to replicate the conditions of rich countries (low birth rates) in poor countries.

Despite what anti-population thinkers suggest, people are not just consumers. Humans are also producers. I’ve chronicled the failure of population policies in a few different pieces for FEE, but the key point is that people on net tend to create more solutions than problems. Humans are not a drag on development and, if anything, may be one of the causes of growth as argued by the late economist Julian Simon.

Low birth rates in rich countries are not evidence that low birth rates cause growth. It’s the other way around. As countries become richer, children are more likely to survive. Parents no longer have to “overshoot” and have more kids than they desire for fear of losing some. Further, as countries develop they tend to move away from cultural male-baby-preference which often drives couples to have many children in hopes of having a first son.

Development agencies such as the UN applauded the coercive anti-population policies of India and China throughout the 20th century. Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon both argued for tying food aid to poor countries to their anti-population goals. This pursuit led to significant damage in the developing world, with no upside of increased growth.

4. Other Answers

There are other popular answers which Easterly does not address as in-depth in the Elusive quest for growth. One common answer is geography. It’s certain that a country’s resources, climate, and physical features likely have some impact on the economic future of the country, but there are many examples which cause me to doubt this is the prime driver.

For instance, the United States is rich with natural resources, and the citizens are rich. Hong Kong, on the other hand, has very little going for it in the way of natural resources, but it also has high levels of wealth. On the other hand, there are some countries with an abundance of natural resources that are poor, and there are some countries that have very little in terms of natural resources which are poor.

So it seems geography isn’t destiny when it comes to wealth.

The Best Answer

So if all these answers are wrong, what is the right answer? Let’s go back to Adam Smith, and take a look at his famous conclusion. Why do countries become rich according to Smith?

“Little else is required to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things.”

Smith is arguing that the ultimate cause of growth in a country stems from its institutions. In other words, the rules that govern your daily economic activity are at the bottom of the different growth outcomes we face in our world.

Another way to frame this is that in order for a country’s economy to grow, the citizens need economic freedom or access to private property rights.

When people have private property, they can use, sell, or rent out their property. This leads to a few results. First, people have an incentive to maximize the value of their property. If you own a house, you want to keep it in good condition because letting it fall apart means you lose some money. Private ownership incentivizes responsibility.

Furthermore, when people are able to sell their goods, prices form for those goods. Prices reflect the value of a good or service relative to other things, and embody societal knowledge about the good. When an oil rig breaks down in the ocean, oil becomes more scarce. We don’t have to be told oil is more scarce to curb our consumption. The rising price causes us to curb consumption whether we know it or not.

Prices also allow firms to do accounting to determine their profit or loss. If a firm makes a profit off of a sale, this tells them consumers valued the final product more than the value of the inputs used to create it. This process of transforming less valuable inputs into more valuable outputs is at the center of economic growth. To paraphrase the economist Peter Boettke: without ownership of the various goods used in production, there can be no markets for them. Without markets for these goods, there are no prices. Without prices, there can be no economic calculation.

So institutions which are economically free are the cause of economic growth. The data bear this out. Economists James Gwartney and co-author Robert Lawson pioneered the Fraser Institute’s “Economic Freedom of the World Index.” The Index measures how free the economies of different countries are and uses that information to examine the connection between freedom and flourishing. What they find fits perfectly with the theory here. Economically free countries are richer and healthier than unfree countries.

Economist Peter Leeson also examines the evidence in a paper titled “Two Cheers for Capitalism?” His conclusion?

“According to a popular view that I call ‘two cheers for capitalism,’ capitalism’s effect on development is ambiguous and mixed. This paper empirically investigates that view. I find that it’s wrong. Citizens in countries that became more capitalist over the last quarter century became wealthier, healthier, more educated, and politically freer. Citizens in countries that became significantly less capitalist over this period endured stagnating income, shortening life spans, smaller gains in education, and increasingly oppressive political regimes. The data unequivocally evidence capitalism’s superiority for development. Full-force cheerleading for capitalism is well deserved and three cheers are in order instead of two.”

In The Elusive Quest for Growth, Easterly has one other insight that merits our attention on this question. Easterly points out how much of the United States government’s focus on development in the late 20th century was really an attempt to win allies against the Soviet Union.

This is extremely ironic, considering that the US government was essentially incorporating Soviet style central planning to attempt to bring about growth in these developing countries.

Instead, it would have been better to follow a US-style pursuit of economic growth. Institutions which enable economic growth are the true driver of wealth creation. Once you enable individuals to freely compete and cooperate, the power of human ingenuity does the rest.

Ask an Economist! Do you have a question about economics? If you’ve ever been confused about economics or economic policy, from inflation to economic growth and everything in between, please send a question to professor Peter Jacobsen at [email protected]. Dr. Jacobsen will read through questions and yours may be selected to be answered in an article or even a FEE video.

Peter Jacobsen

Peter Jacobsen is a Writing Fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.