Plastic pollution is one of the biggest environmental challenges we face today, with millions of tons of waste ending up in landfills, oceans, and natural habitats every year. But nature might hold a key to helping clean it up. In 2011, a team of Yale University students discovered a remarkable fungus in the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest that can break down certain types of plastic. This fungus, known as *Pestalotiopsis microspora*, has sparked interest among scientists for its potential role in reducing plastic waste.

How Was This Fungus Discovered?

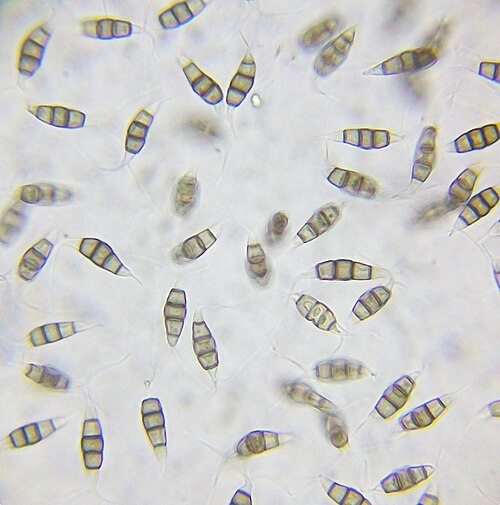

The discovery happened during Yale’s annual Rainforest Expedition and Laboratory, where students collected samples from plant stems in the Yasuni National Forest, part of the Ecuadorian Amazon. These samples contained endophytic fungi—microorganisms that live inside plants without harming them. The researchers isolated various fungi and tested them for unique abilities. Through DNA sequencing of a specific genetic region called the internal transcribed spacer (ITS), they identified *Pestalotiopsis microspora* as one of the standout species. Student Pria Anand documented its behavior, while Jonathan Russell isolated the enzymes responsible for its plastic-breaking powers. Their findings were published in the journal *Applied and Environmental Microbiology*.

What Makes This Fungus Special?

Pestalotiopsis microspora can degrade polyester polyurethane (PUR), a tough plastic commonly used in products like garden hoses, shoes, and foam insulation. Unlike many other organisms, it can use PUR as its sole source of carbon and energy, essentially “eating” the plastic to survive. In lab tests, the fungus cleared PUR from growth media in about two weeks, turning the opaque mixture translucent as it broke down the material.

What sets it apart is its ability to do this in both oxygen-rich (aerobic) and oxygen-free (anaerobic) environments. This is crucial because landfills—where much plastic waste ends up—are often anaerobic at deeper levels. The fungus achieves this through an extracellular enzyme, identified as a 21-kDa serine hydrolase, which breaks the chemical bonds in PUR, specifically targeting ester linkages. Infrared spectroscopy confirmed the degradation by showing the disappearance of key chemical peaks in the plastic structure.

In experiments, two specific isolates of the fungus (E2712A and E3317B) outperformed others, degrading PUR with a half-time of about five days when it was the only food source available. This was faster than known degraders like *Aspergillus niger*, a common mold used as a control in the study.

Potential for Solving Plastic Pollution

This fungus offers promise for bioremediation—the use of living organisms to clean up pollutants. Since it works in anaerobic conditions, it could potentially be applied in waste treatment systems or landfills to break down PUR-based plastics. Researchers suggest that endophytic fungi like this one are a rich source of biodiversity for finding more tools to tackle synthetic polymers. Some envision large-scale uses, such as fields of fungi or integration into trash compactors, though these ideas remain conceptual.

However, research since the 2011 discovery has largely focused on understanding its mechanisms rather than widespread applications. A 2024 review highlighted its unique anaerobic degradation as a standout feature compared to other plastic-degrading organisms, but no major commercial breakthroughs have been reported. Other studies continue to explore similar fungi, including in ocean environments, but Pestalotiopsis microspora remains a key example of nature’s potential solutions.

While it’s not a complete fix for all plastic pollution—since it targets specific types like PUR and not others like polyethylene—the discovery underscores the importance of preserving rainforests, where such innovative organisms thrive. Ongoing research may unlock more ways to harness this fungus for a cleaner planet.