As the recent power outage in Washington D.C. so aptly demonstrated, we’re not equipped to deal with serious power outages — and we’re not equipped to prevent them, either.

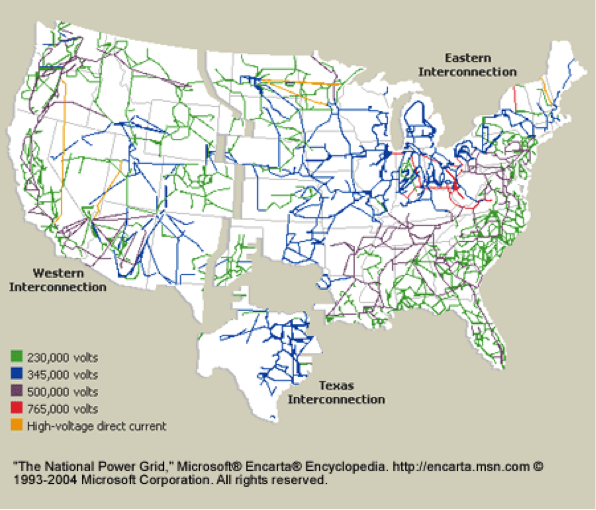

The American Power Grid is comprised of three smaller grids, called interconnections, that move electricity around the country. The Eastern Interconnection operates in states east of the Rocky Mountains, The Western Interconnection covers the Pacific Ocean to the Rocky Mountain states, and the smallest — the Texas Interconnected system — covers most of Texas, as displayed in the map below.

The electric grid is an engineering marvel but its aging infrastructure requires extensive upgrades to effectively meet the nation’s energy demands. Through the Recovery Act (TARP), the Energy Department invested about $4.5 billion in grid modernization to enhance the reliability of the nation’s grid. Since 2010, these investments have been used to deploy a wide range of advanced devices, including more than 10,000 automated capacitors, over 7,000 automated feeder switches and approximately 15.5 million smart meters.

What is the distinction between grid reliability and resiliency?

A more reliable grid is one with fewer and shorter power interruptions. A more resilient grid is one better prepared to recover from adverse events like severe weather.

Severe weather

Weather events are the number one cause of power outages in the United States, costing the economy between $18 and $33 billion every year in lost output and wages, spoiled inventory, delayed production and damage to grid infrastructure. Yet every year they still come as a massive surprise. But now, it seems we are under threat from an enemy we can’t predict by checking The Weather Channel.

Cyber attacks

Since 2010, the Energy Department boasts that it has invested a $100 million to advance a resilient grid infrastructure that can survive a cyber incident while sustaining critical functions. Yet since that time the grid has been under almost constant attack with hackers being able to flick critical switches on and off, seemingly at will. And the energy industry is the No. 1 target.

The Department of Homeland Security’s Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT) has warned that attacks against critical infrastructure are growing, with more than 200 brute-force cyberattack incidents recorded in just six months back in 2013.

For example, 49 malicious IPs attacked natural gas companies across the Midwest and Plains. “While none of the brute force attempts were successful,” in only the first half of fiscal year 2013, ICS-CERT deployed onsite teams five different times, three times to energy sector companies and twice to manufacturers. “All of the onsite incident response engagements involved sophisticated threat actors who had successfully compromised and gained access to business networks.” In comparison, the ICS-CERT onsite teams were deployed only six times for all of fiscal year 2012.

During 2014, ICS-CERT warned of increasing brute-force cyber attacks against US critical infrastructure, energy industry.

“How many times do pumping stations fail, blackouts happen, or elevators and HVAC systems shut down because a hacker is on a network flicking switches on and off?” asked Threatpost. Security researcher Billy Rios suggested, “If it was simple, I doubt DHS would have been brought in to investigate. It probably did disrupt something. I’m not sure how widespread it was, but if it was small, I think an integrator could come in and reset everything. Instead DHS came in to investigate.”

A critical zero-day vulnerability was detected in the Tridium Niagara AX Framework; Tridium is used by the military, hospitals and others. Access would allow attackers to remotely control electronic door locks, lighting systems, elevators, electricity and boiler systems, video surveillance cameras, alarms and other critical building facilities.

But instead of putting the bulk of their money into modernization of the system and putting it beyond the reach of a cyber-attack, the Administration has focused on synchrophaser technology. These mailbox-size devices monitor the health of the grid at frequencies not previously possible, reporting data 30 times per second. This enhanced visibility into grid conditions helps grid operators identify and respond to deteriorating or abnormal conditions more quickly, reduce power outages and help with the integration of more renewable sources of energy into the grid. To date, nearly 900 of these devices have deployed as a result of TARP investments. This is good news for genuine weather-caused outages but not so useful for cyber attacks.

What are they doing?

It’s unknown why critical infrastructure cybersecurity is still as such a high risk of attack, since in 2010, experts said, “By the end of 2015, the potential security risks to the smart grid will reach 440 million new hackable points.” In 2011, it was announced that we should be “very scared” . . . that a $60 piece of malware could bring down the power grid. In 2012, there was a secret demo for senators that simulated a cyberattack on the power grid, causing a mock blackout in NYC during the midst of a killer heat wave. Then even FEMA trained for a zero-day attack by hacktivists against critical infrastructure.

Password mistakes – are you as guilty as the government?

Would you believe that in some case, our critical infrastructure systems connected online are still using default passwords! That’s like you leaving your home internet router on the default password you got when you took it out of the box. (If you did, change it, fast.) “Any system using password authentication accessible from the internet may be affected. Critical infrastructure and other important embedded systems, appliances, and devices are of particular concern.” US-CERT warned that it is “imperative” to change the manufacturer’s password, as the lists of such default passwords are easily obtained online and attackers can use the Shodan search engine to find exposed systems.

Could your body be hacked?

And it’s not just infrastructure. Medical devices like pacemakers can be hacked. If a device contains configurable embedded computer systems it can be vulnerable to cybersecurity breaches. In addition, as medical devices are increasingly interconnected, via the Internet, hospital networks, other medical device, and smartphones, there is an increased risk of cybersecurity breaches, which could affect how a medical device operates.”

Think we’re exaggerating?

In 2008, a group showed how to remotely hack a pacemaker and deliver a lethal shock to an implantable cardiac defibrillator. A 2011 Black Hat presentation explained how an attacker with a powerful antenna could be up to a half mile away from a victim yet launch a wireless hack to remotely control an insulin pump and potentially kill the victim. In 2012, a pacemaker hacker said a worm could possibly ‘commit mass murder.’ Being killed by code was an idea kicked around since 2010. Also in 2012, the feds were pressed to protect wireless medical devices from hackers.

In 2008, a group showed how to remotely hack a pacemaker and deliver a lethal shock to an implantable cardiac defibrillator. A 2011 Black Hat presentation explained how an attacker with a powerful antenna could be up to a half mile away from a victim yet launch a wireless hack to remotely control an insulin pump and potentially kill the victim. In 2012, a pacemaker hacker said a worm could possibly ‘commit mass murder.’ Being killed by code was an idea kicked around since 2010. Also in 2012, the feds were pressed to protect wireless medical devices from hackers.