The North American bison, widely known as the buffalo, will now likely be recognized as America’s “national mammal”—on par with the bald eagle. (The bill is heading to the president’s desk.)

It is a fine tribute to a creature etched into American lore. While praises are already being made to the efforts of conservationists and modern environmentalists to save North America’s largest land mammal, the reality is that the species was saved by capitalism.

After describing how bison populations “dwindled from tens of millions to the brink of extinction,” a Huffington Post contributor wrote that the animal must be “acknowledged as the first success story of the modern conservation movement.”

Conservationists did play a role in saving the buffalo from extinction, but it was in large part the power of the free market that allowed the once-decimated species to thrive after nearly being wiped out.

Any description of the Great Plains in the 19th century usually involves vast herds of the giant, imposing bison dotting the landscape. The great frontier historian, Francis Parkman, included numerous, vivid descriptions of buffalo herds and hunts in his books.

Parkman wrote in “The Oregon Trail,”

The face of the country was dotted far and wide with countless hundreds of buffalo. They trooped along in files and columns, bulls, cows, and calves … They scrambled away over the hills to the right and left; and far off, the blue pale swells in the extreme distance were dotted with innumerable specks.

Native American tribes of the Great Plains relied on the American bison for food when early American pioneers encountered them in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Plains Indians had unique hunting methods that were efficient, yet wasteful.

Anyone who has spent time in Wyoming, Montana, or any one of the Plains states is likely to have encountered giant, seemingly random craters. These are the remains of what were called “buffalo jumps,” and were the primary way many tribes cultivated the animal for food.

Frontier explorer Meriwether Lewis, of the famed Lewis and Clark expedition, described one of these jumps in an 1805 journal entry:

Today we passed on the Stard. side the remains of a vast many mangled carcases of Buffalow which had been driven over a precipice of 120 feet by the Indians and perished; the water appeared to have washed away a part of this immence pile of slaughter and still their remained the fragments of at least a hundred carcases they created a most horrid stench. in this manner the Indians of the Missouri distroy vast herds of buffaloe at a stroke.

It was a ruthless affair, but it got the job done. Squandering enormous quantities of meat was simply not a problem for the nomadic people of the plains. There seemed to be endless amounts of the beasts.

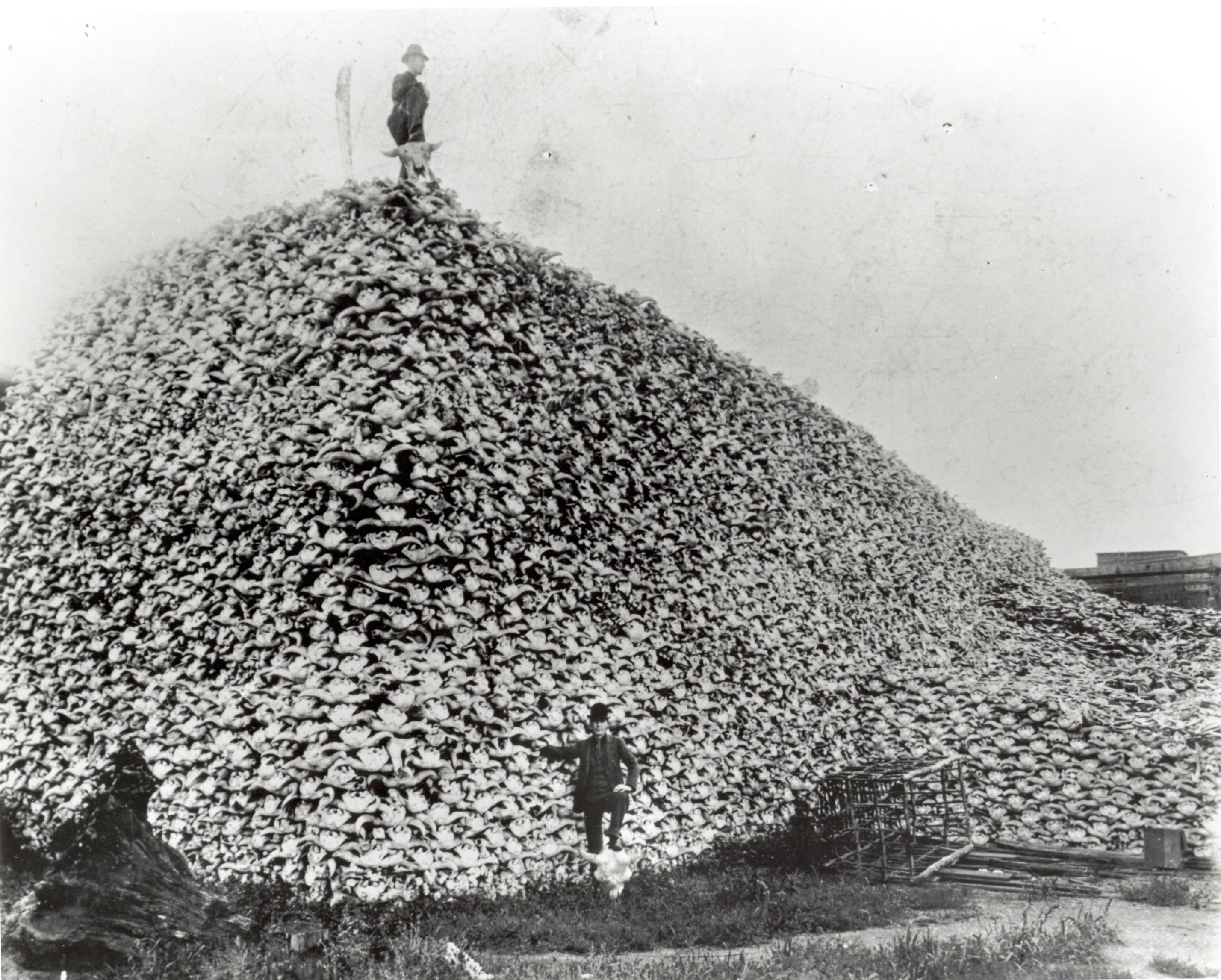

Undated photo of a man standing on an enormous pile of buffalo skulls. (Photo: Picture History/Newscom)

The dwindling of the American bison began long before settlers arrived, but a swelling population of new migrants finally put the species at risk. And the intentional extermination of the herds to drive out the Plains Native Americans left the buffalo on the brink of annihilation. At one point, there were only 300 of them left in the wild.

Saved by a Free Society and Market Economics

Though the social and economic dynamics of the 19th century came close to wiping out the American bison, the species survived and began a recovery in the 20th century. The wild-roaming bison had been hunted mercilessly to the brink of destruction, but widespread private ownership allowed them to flourish.

Historian Larry Schweikart wrote about a study by Andrew C. Isenberg, now a professor at Temple University, which busted the myth that it was government intervention that saved the bison. From a small herd clinging to survival in Yellowstone National Park, the bison began their resurgence. Isenberg’s conclusion “upsets the entire apple cart of prior assumptions,” according to Schweikart:

This remnant herd and other scattered survivors might eventually have perished as well had it not been for the efforts of a handful of Americans and Canadians. These advocates of preservation were primarily Western ranchers who speculated that ownership of the few remaining bison could be profitable and elite Easterners possessed of a nostalgic urge to recreate . . . the frontier.

Preservation societies that aimed to maintain an authentic Western landscape, and travelling shows like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, were instrumental in keeping the tiny bison population alive. They did a much better job of protecting these valuable assets than the public national parks.

But even more than as a tourist attraction, the bison became prized for the same reason Plains Native Americans and settlers hunted them to begin with: They’re delicious.

Isenberg’s study showed that the number of bison swelled in the 20th century mostly because they were “preserved not for their iconic significance in the interest of biological diversity but simply raised to be slaughtered for their meat.”

Ranchers like Charles Goodnight, who provided the herd reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park in 1902, found ways to raise and profit from the bison. This led to a thriving national industry and ensures the bison will survive into the 21st century. Today there are around 500,000 buffalo in the United States, and about 90 percent are in private hands. And for that miracle resurrection, the world has capitalism, not Congress, to thank.