by Dan Mitchell

In January, I shared a short video about protectionism, which expanded on some analysis from a one-minute video from last year.

Today, here’s a short video explaining the trade deficit, which also expands on a one-minute video from last year.

Simply stated, trade deficits are largely irrelevant.

And since trade balances don’t matter, then it makes no sense to fight trade wars. Especially when protectionist-minded politicians inflict lots of casualties on their own people.

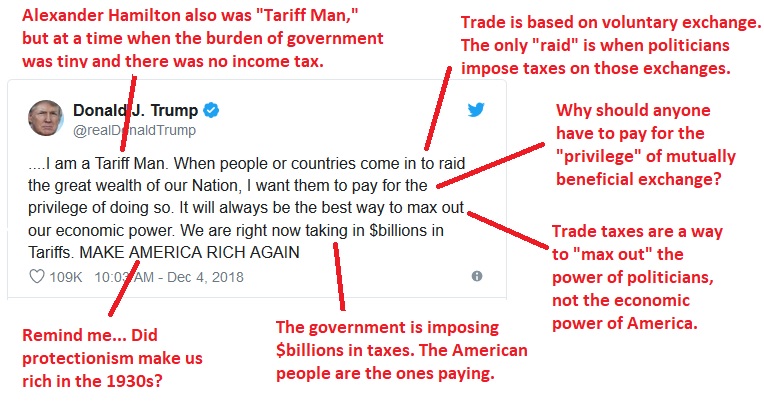

Given all the dramatic rhetoric in Washington about trade deficits – especially from President Trump, it’s worth pointing out that there’s nothing radical or unconventional about my analysis.

Kevin Williamson, for instance, made similar points when he explained the economics of trade deficits for National Review.

A trade deficit is just a bookkeeping entry, not a debt that has to be paid. Countries don’t trade — people do. Americans are no more harmed by the trade deficit with Germany than you are by your trade deficit with Kroger. …trade deficits…are not really driven by consumer behavior… It’s true that many Americans prefer German cars and French wines — and cheap electronics and T-shirts made in China — but trade deficits mostly are the result of several other causes: macroeconomic factors such as tax policies and savings rates, the strength of a country’s currency, and, most important, its attractiveness to investors. …Far from being victimized by such trade, Americans are enriched by it.

Indeed, while more trade is associated with more prosperity, Kevin notes that there’s no link with trade balances.

Trade deficits are not a sign of economic trouble, and trade surpluses are not necessarily a sign of economic health. The last time the U.S. ran a trade surplus with the world was 1975, when our economy was in a shambles. Britain ran a trade deficit from Waterloo to the Great War, a century marking the height of its power, and it grew vastly wealthy.

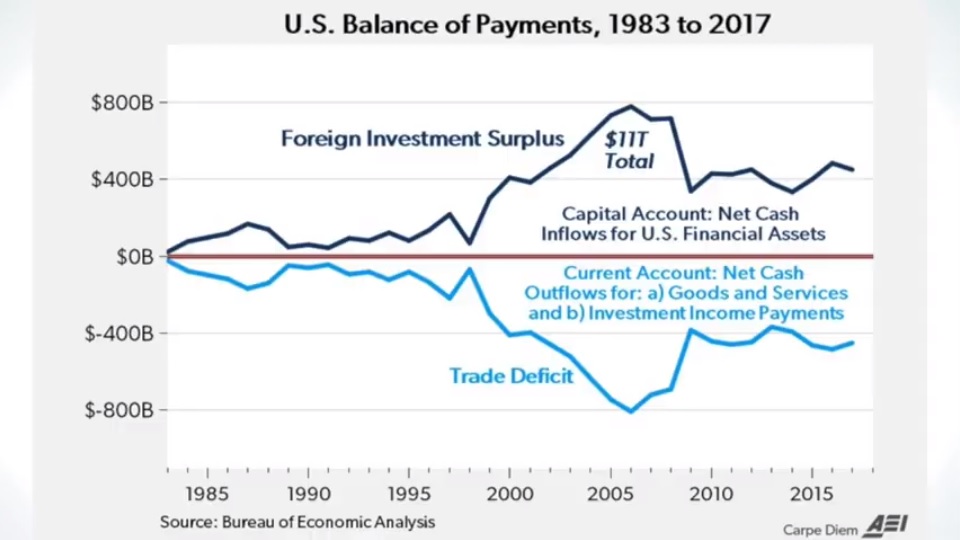

Neil Irwin, writing for the New York Times, points out that a trade deficit is the same as a capital surplus.

A core idea that Donald J. Trump has embraced throughout his time in public life has been that the United States is losing in trade with the rest of the world, and that persistent trade deficits are evidence of this fact. …The vast majority of economists view it differently. In this mainstream view, trade deficits are not inherently good or bad. …When a country runs a trade deficit, there is a countervailing force. …the flow of capital is the reverse of the flow of goods. And the trade deficit will be shaped not just by the mechanics of what products people in the two countries buy, but also by unrelated investment and savings decisions. The cause and effect goes both directions. …the flow of capital into the country — the inverse of the trade deficit — creates benefits that can be good for jobs, by encouraging more domestic investment.

Amen. I wrote back in 2017 about why it’s good when foreigners invest and create jobs in America.

Irwin also explains that the U.S. gets significant benefits because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency.

…the dollar isn’t used just in trade between the United States and other countries. The dollar is a global reserve currency, meaning that it is used around the world in transactions that have nothing to do with the United States. When a Malaysian company does business with a German company, in many cases it will do business in dollars; when wealthy people in Dubai or Singapore’s government investment fund want to sock away money, they do so in large part in dollar assets. That creates upward pressure on the dollar for reasons unrelated to trade flows between the United States and its partners. That, in turn, makes the dollar stronger…maintaining the global reserve currency creates…a lot of advantages. Lower interest rates and higher stock prices are among them.

For what it’s worth, politicians should ignore the trade deficit and focus instead on preserving the dollar’s special status as a reserve currency.

Let’s also review some commentary from Jeff Jacoby in the Boston Globe.

For centuries, economists have pointed out the destructive folly of tariffs and other trade barriers. Tirelessly they explain that a trade deficit is not a defeat, just as a shopper’s “deficit” with a department store is not a defeat. They implore policymakers to see that trade restrictions always impose more costs on a country’s economy than any benefits they generate. …Nations don’t trade with each other. We speak as if they do out of habit and convenience, but it’s not true. The United States and Canada are not competing firms. America doesn’t buy steel from China, and China doesn’t buy soybeans from America. Rather, hundreds of individual American companies choose to buy steel from Chinese mills and fabricators, and hundreds of Chinese-owned firms make deals to buy soybeans from far-flung American growers.

He explains that trade is peaceful and productive cooperation.

…international trade occurs among countless sellers and buyers, all acting independently in their own best interest. …To those individuals, national trade deficits and surpluses are irrelevant. They aren’t competing — they’re cooperating. Buyers and sellers aren’t in conflict with each other, let alone with each other’s countries. On the contrary: By doing business together, traders create wealth and connections, knitting the world together in mutual interest, making the planet more harmonious.

Reminds me of Bastiat’s observation about trade and war.

But that’s a separate issue. The focus today is on the meaning (or lack thereof) of trade deficits.

Let’s close with a chart from the video (which I first shared exactly one year ago), which clearly shows that a trade deficit is simply the flip side of an investment surplus.

P.S. I’m still waiting for an anti-trade person to answer these questions I asked back in 2011.

P.P.S. And I also challenge anyone to defend Trump on this issue when compared to Reagan.