In an editorial last week, the Los Angeles Times declared it conventional wisdom that COVID-19 proves Bernie Sanders was right about “Medicare for All,” because with universal health coverage, the government wouldn’t have to send emergency aid to “hospitals and state health programs.”

This assertion is completely false, however, and we know because billions in emergency aid from the federal government is precisely what’s happening in Canada.

Canada is experiencing a surge in serious COVID-19 cases, with eight new deaths per million April 8 compared to nine deaths per million in the much-larger U.S. Total deaths in Canada were up to 435 per day.

Canadian society essentially is on lockdown, with schools and public events closed, police fining house parties, and provinces, including Quebec, closing all nonessential businesses.

Like the U.S., Canada began to see widespread shortages in health-related supplies, from masks and personal protective equipment to testing reagents and vaccine manufacturing capacity.

Also like the U.S., the overarching concern in Canada has been “bending the curve” of infections, using compulsory social distancing mandates that raise constitutional questions.

Finally, like the U.S. and contrary to the Los Angeles Times, Canada’s federal government has committed to billions for cash-strapped health agencies and hospitals across the country, with intense pressure for more.

Indeed, that spending sparked a bitter showdown in Parliament as the opposition balked at the government’s request to spend “all money required to do anything.”

What gives Canada such urgency to keep the infection curve down is that, going on decades now, the single dominating feature of Canadian health care is shortages.

As early as March 20, Reuters news service quoted the chief of staff of one of Ontario’s newest hospitals as saying, “You’ve got people in broom closets and auditoriums and conference rooms across the country.”

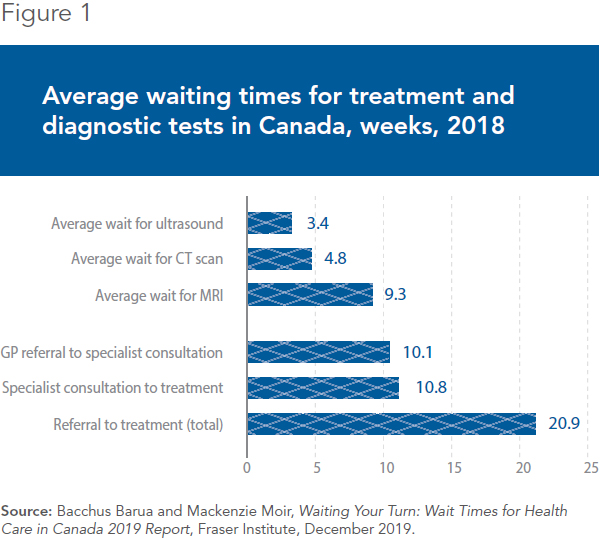

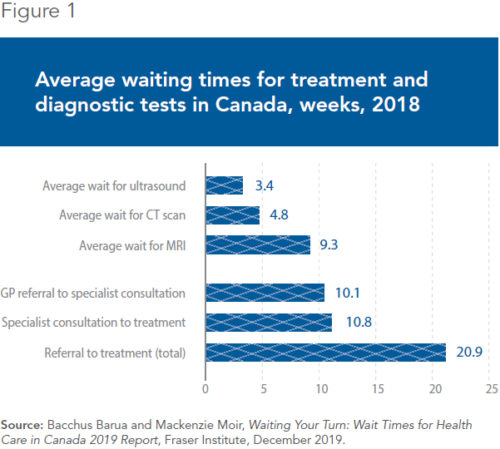

Even in normal times, the average wait in Canada from referral to treatment by a specialist is 20 weeks, compared to less than four weeks in the U.S. Long before COVID-19, an estimated 1 million Canadians languished on waiting lists, waiting in pain or flying abroad for faster treatment.

Canadians long have faced shortages and lengthy waits for MRIs and ultrasounds while being forced to use outdated and cheaper drugs. Canadian emergency rooms have been packed for years, with four-hour waits running three times the U.S. level and four-hour waits standard in Quebec province.

This is all in normal times, before COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus.

These shortages mean there is very little spare capacity in Canada to handle any surge in emergency treatment. The concern is most acute for beds in intensive care units, the kind needed to treat critical COVID-19 cases.

Per capita, Canada has one-third as many ICU beds as the U.S. and about the same number as ravaged Italy. In some provinces, including Alberta and British Columbia, ICU beds number fewer per capita than Iran.

Given these problems, “bending the curve” of coronavirus infections becomes an existential priority for Canada. There is very little talk of reopening the Canadian economy anytime soon, simply because the spare critical care infrastructure is not there.

Already in early April, over 3 million Canadians had applied for unemployment benefits, equivalent to 27 million Americans.

Unfortunately, at this point, there is little Canada can do. The private health care sector for critical care is atrophied, largely banned by a monopoly public sector that long has cut corners to save money.

Thousands of retired doctors and nurses have volunteered heroically to return to work, but there essentially is no private sector to ramp up capacity quickly. Canadians are left to hope for the best as the slow machinery of the public health system grinds on.

Too little too late, Canada is doing what it can to bring in the private sector. Emergency deregulations are spreading across health care, from scope of practice to product licensing, while private operators finally are getting limited permission to operate in telemedicine.

But 50 years of government management of essential health care has left Canada with far less capacity and far fewer resources than it needs in this crisis.

As for Medicare for All, the COVID-19 crisis in Canada has shown the brutal consequences of government-run health care: shortages just when you need care the most.

Peter St. Onge, Ph.D., is senior economist at the Montreal Economic Institute. A former assistant professor at Taiwan’s Feng Chia University and general partner of a private equity fund in Washington, D.C., he holds a doctorate in economics from George Mason University. Reproduced with permission from the Daily Signal.