By J. Alexander Navarro, Professor of History of Medicine, University of Michigan

Coronavirus infection rates continue to rise, with the number of new cases climbing in dozens of states and the U.S. reporting record numbers of cases on individual days. Hospitalization across the U.S. has dramatically jumped; some cities are seeing surges that threaten to overwhelm their health care systems.

Meanwhile, the demonstrations over the police killing of George Floyd brought tens of thousands into the streets, congregating shoulder-to-shoulder. Many are the victims of tear gassing by police, potentially increasing the risk of transmission and infection. The latest models indicate COVID-19’s U.S. death toll could reach 170,000 by October. A second wave this fall – or the continuation of an unabated first wave – could make that number even higher.

But these are not unprecedented times.

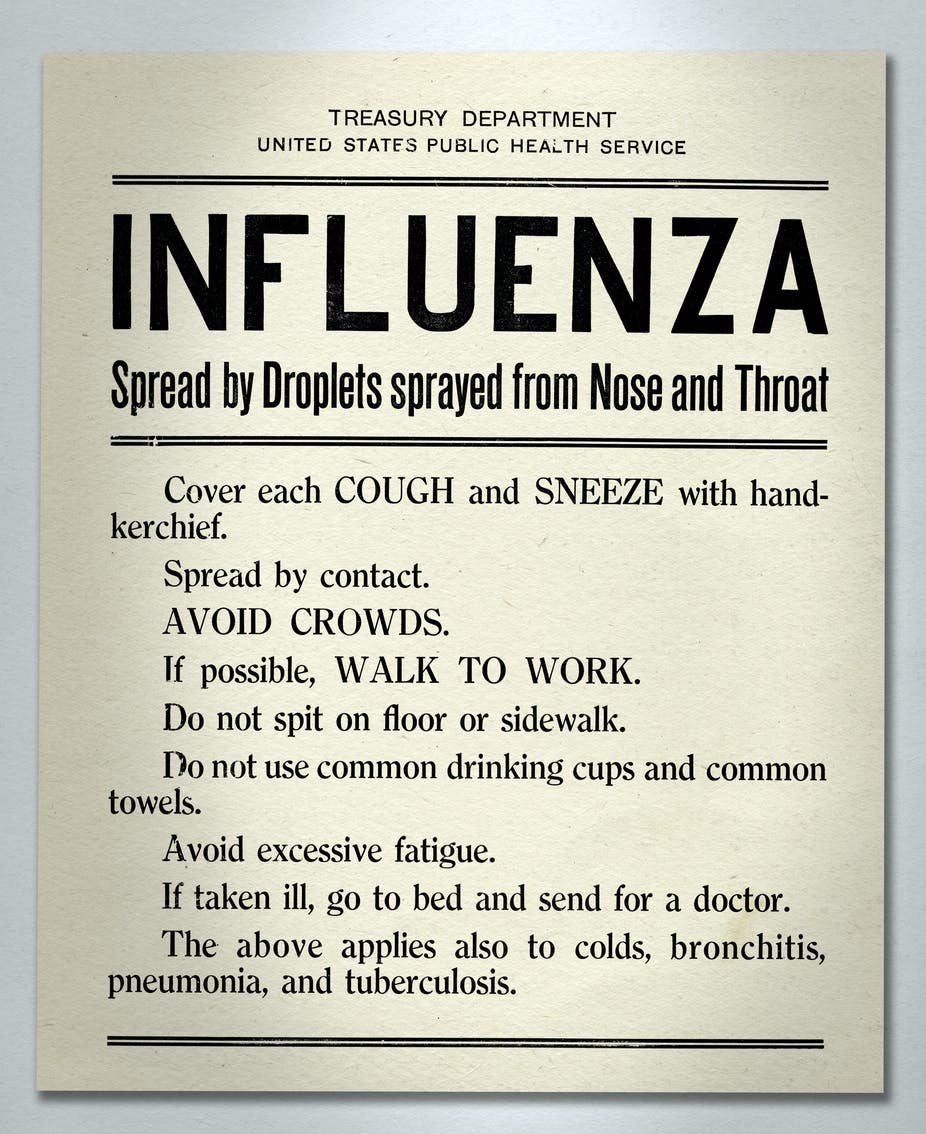

As a historian of medicine at the University of Michigan, I am a student of the 1918 influenza pandemic. It remains the deadliest public health event in recorded history. There are lessons to be learned from what happened a century ago. True, there are differences between then and now. Then we were a nation at war, with an economy led by manufacturing and a male-dominated workforce. We had far less medical and scientific knowledge. And it was an entirely different virus. But striking similarities exist between how we reacted to the pandemic in 1918, and how we’re responding now.

Lessons from the last century

The city of Denver, Colorado, is perhaps the most relevant case study. As the epidemic skyrocketed, officials ordered the immediate closure of schools, churches, and places of public amusement. Indoor public gatherings were banned. Such action, it was argued, would save lives and money.

The business community agreed. One theater owner put it this way: “I shall sacrifice gladly all that I have and hope to have, if by so doing I can be the means of saving one life.”

That noble sense of civic duty quickly faded as townspeople took to congregating outdoors. They met in the busy downtown shopping district and at outdoor church services and lodge meetings. Business owners and those thrown out of work by the closure orders decried these gatherings; they were bearing the brunt of the closures, they said, while the public shirked its duty. Denver’s health officer, calling out the “criminal neglect” of those at the open-air assemblies, added outdoor gatherings to the prohibitions.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Within just two weeks of the closures, residents grew restless. As records of new cases leveled off, many demanded an end to both the closure order and gathering ban. Giving in to the pressure, the mayor and health officer announced the measures would be lifted on Nov. 11, 1918. That day – in a horrible twist of fate – turned out to be Armistice Day. Thousands thronged the streets, hotels, theaters, and auditoriums of Denver to celebrate both the end of World War I and the pandemic. But only one of them was truly over.

Health authorities realized a new surge of influenza deaths were likely but acknowledged there was little they could do. “There is no use trying to lay down any rules regarding the peace celebration,” said one official, “as the lid is off entirely.”

The next wave hits

The surge came hard and fast. Within a week, physicians reported hundreds of new cases and dozens of deaths per day. Officials responded with another set of closure orders and gathering bans. Theaters, bowling alleys, pool halls, and other places of public amusement were shut down. Affected business owners, complaining they were singled-out, formed an “amusement council,” and demanded the city close all places of congregation or issue a mask order. City officials acceded. They put a mask order in place.

Enforcement was an issue. Residents routinely refused to wear masks even when threatened with arrest and hefty fines. The mayor soon realized the futility of the order. “Why, it would take half the population to make the other half wear masks,” he said. “You can’t arrest all the people, can you?” Officials then backed off again: they would recommend mask use, not require it.

Except for streetcar conductors. They still had to wear them, said the city. Bristled at being singled out, the conductors threatened to strike. A walkout was averted when city officials again watered down the order. Conductors only had to wear them during rush hour commutes. The new provisions were all but useless, and a few days later the mask rule was abolished.

Denver’s epidemic continued for several months. It was unchecked by any public health orders, save for isolation and quarantine for those with the illness. The result: a second spike of deaths higher than the first, and one of the nation’s largest per capita death tolls.

History could repeat itself

Surely at least some of this sounds familiar. If Denver’s story tells us anything, it is that we must do better than in 1918. All of us must continue to combat COVID-19 with face masks and social distancing in public. Recent studies show face masks, along with hand sanitation and social distancing by a majority of the population, can quickly bring this pandemic under control.

Those levels of compliance, however, might become increasingly difficult. In 2020, we are bristling much the same way they did in 1918. A century ago, masks were widely despised; many today feel the same way. Yet if we don’t take these measures seriously, we will likely face a resurgence of the virus.

If the past offers us any perspective into the future, it is this: returning to the sweeping closures and stay-at-home orders that we’re emerging from may be difficult. It proved all but impossible to do so a century ago. It very well may prove impossible today.

J. Alexander Navarro, Professor of History of Medicine, University of Michigan

Read the original article.