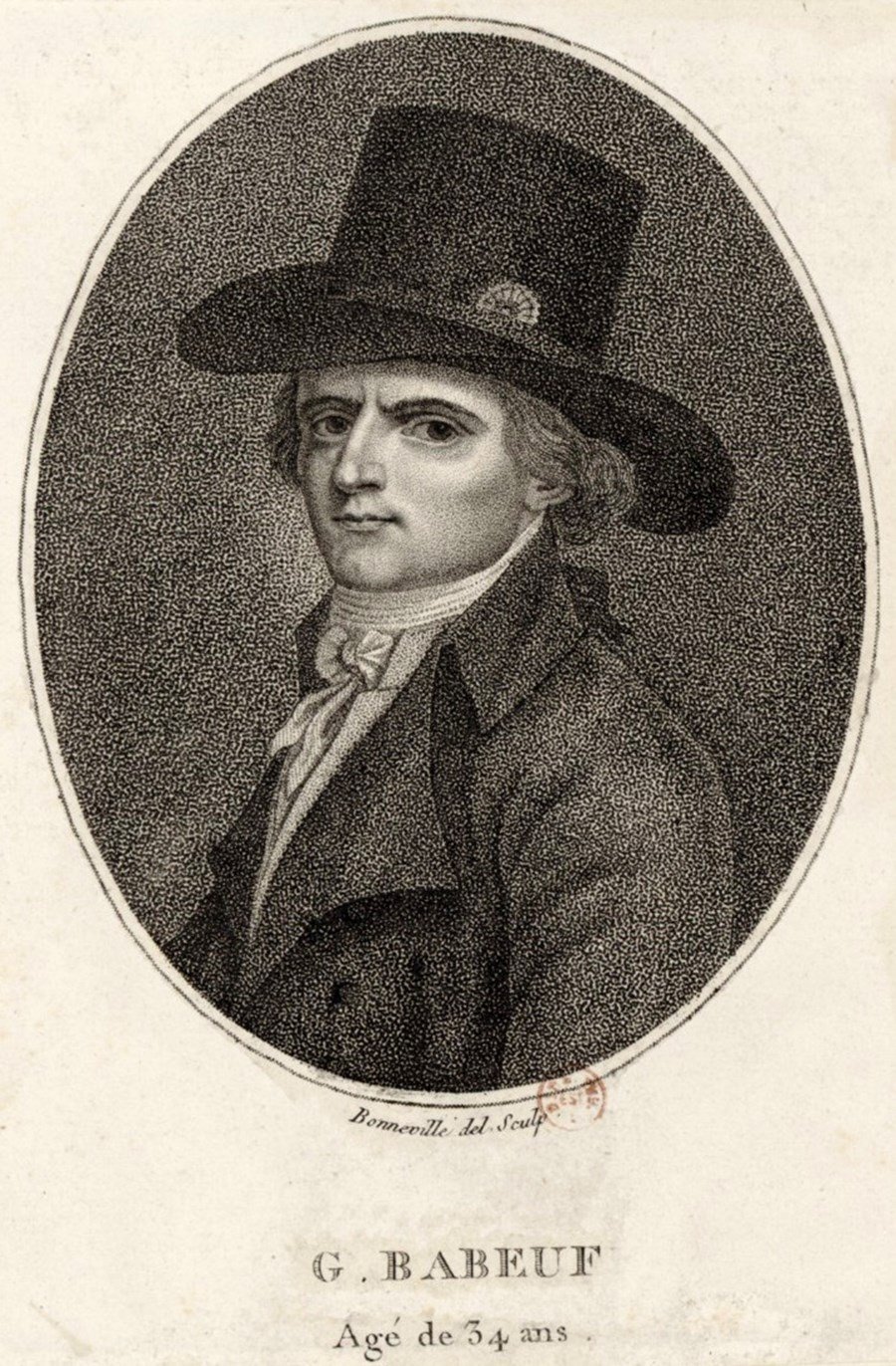

The French Revolution produced a parade of fascinating characters, many of them deranged by power and vampire-like in their quest for blood. One of the period’s lesser-known figures was Gracchus Babeuf, whose ideas were shelved with his death in 1797 only to reappear decades later in the writings of Karl Marx. Babeuf was, as the title of a biography attests, the world’s first revolutionary communist.

under the digital ID btv1b84127115 [public domain]

Babeuf’s Mental Condition

He was born Francois-Noel Babeuf in 1760 in northeastern France. He changed his first name twice in later life—first to “Camille” and later to “Gracchus.” The latter was in deference to the brothers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, who sought to redistribute land in the late Roman Republic. As a young adult in the 1780s, he made his living as an expert in feudal law, keeping records of what the peasants owed in rent and fees to the privileged nobility. The injustices of this medieval form of state-sanctioned oppression were, of course, endemic and profuse, and they upset Babeuf immensely.

Babeuf’s mental condition on the eve of the French Revolution is open to question. This is important because his political philosophy was beginning to take shape at this time. One disturbing indication that his seat back and tray table may not have been in their locked and upright positions involved the loss of his four-year-old daughter Sofie. She died in 1787, and her untimely death grieved him profoundly. Even Babeuf admirer and biographer Ian Birchall (The Specter of Babeuf) terms his reaction “bizarre”:

Babeuf apparently cut the heart out of the corpse, ate part of it, and wore the rest in a locket on his chest. It was an odd mixture of superstition and materialism, indicative of the way that Babeuf’s view of the world was developing. Without hope that his daughter’s soul might achieve immortality [he was rabidly atheist], he was seeking to preserve the object of his affections by fusing his body with the remnant of hers.

Babeuf in Politics

When the French Revolution began in the summer of 1789, Babeuf’s interest in politics soared. He played a bit part in the first five years, spending much of his time privately fleshing out and radicalizing his political philosophy. When the guillotine claimed the architect of the Reign of Terror, Maximilien Robespierre, in July 1794, Babeuf burst onto the scene with his newspaper, Tribun du Peuple.

He became a minor celebrity immediately. At first, he denounced Robespierre in vicious terms, a perspective that later changed to a fawning adoration of the departed Jacobin once the new government called the Directory consolidated its power.

The economic conditions the Directory inherited in mid-1795 were desperate. Within a year, they were even worse. Hyperinflation roared as the new government pumped out billions of paper notes. War with Europe drastically reduced commerce. Food supplies dwindled. Starvation killed thousands. In that environment, Babeuf saw an opportunity. He would use it to call for a radical egalitarianism and ultimately, another revolution. His efforts toward those ends would be known in history as “The Conspiracy of the Equals.”

In Volume 2 of An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought (1995), excerpted here, economist Murray Rothbard summarized the views of this Marxist-before-Marx and his Conspiracy of the Equals.

The ultimate ideal of Babeuf and his Conspiracy was absolute equality. Nature, they claimed, calls for perfect equality; all inequality is injustice: therefore, community of property was to be established….In the ideal communist society sought by the Conspiracy, private property would be abolished, and all property would be communal and stored in communal storehouses. From these storehouses, the goods would be distributed “equitably” by the superiors—apparently, there was to be a cadre of “superiors” in this oh so “equal” world!

Of the half dozen books on Babeuf, most are hagiographies by adoring Marxists who offer one lame excuse after another for their subject’s eccentricities. The best and most objective treatment of Babeuf was also the first full-length biography of the man, Gracchus Babeuf: The First Revolutionary Communist. Written in 1978 by Professor R. B. Rose of the University of Tasmania, it’s worth the attention of anyone interested in Babeuf as a precursor to Karl Marx.

Marx and Babeuf

Separated by half a century, the similarities between the two communist theoreticians are striking. On many matters, it’s as if Marx simply pilfered the thoughts of Babeuf and then superimposed the complaints of his French predecessor onto capitalism instead of onto medievalist France.

Most of the big stuff you find in Marx, you can find in Babeuf: Workers are exploited; the value of their labor is expropriated by profiteers. Private property is the root of all evil. To create the communist utopia, there must first be a period of dictatorship marked by violence to expunge society of its bad ideas and behavior. Christianity is an opiate for the masses. Blah, blah, blah. Boilerplate babble—superficial, arrogant, and devoid of genuine economic analysis. To quote from Rothbard again:

An absolute leader, heading an all-powerful cadre, would, at the proper moment, give the signal to usher in a society of perfect equality. Revolution would be made to end all further revolutions; an all-powerful hierarchy would be necessary allegedly to put an end to hierarchy forever.

But of course, as we have seen, there was no real paradox here, no intention to eliminate hierarchy. The paeans to “equality” were a flimsy camouflage for the real objective, a permanently entrenched and absolute dictatorship, in Orwell’s striking image, “a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

Almost nothing in the manifestos, declarations, and proposals of Babeuf and his conspirators was original. They were echoes of earlier thieves, mountebanks, and crackpot philosophers. As even socialist and Babeuf sympathizer Ernest Belfort Bax admits in his biography, Gracchus Babeuf and the Conspiracy of Equals:

The only point that was new in the theory of the Equals…was the notion of the transformation of the entire French republic, by the seizure of political power, into one great communistic society….Babeuf was the first to conceive of Communism in any shape as a politically realizable ideal in the immediate or near future….

What distinguishes Babeuf from his revolutionary predecessors is his placing communism, involving the definite abolition of the institution of private property, in the forefront of his doctrine…and in his bold idea of its prompt realization by political means, through a committee of select persons placed in power by the people’s will as the issue of a popular insurrection….Gracchus Babeuf and his movement cannot fail to be for the modern socialist of deepest possible historical interest. Gracchus Babeuf was, in a sense, a pioneer and a hero of the modern international Socialist party.

Bax also offers this telling concession: “With all our admiration of Babeuf’s energy and heroism as a revolutionary figure, it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that he was intellectually unstable.” How about just plain nuts?

The Tribun

Babeuf’s newspaper, Tribun, became the official mouthpiece of his new movement. Nightly meetings were held at which articles and commentary from Tribun were read and discussed by the faithful.

Once Babeuf determined that a violent overthrow of the government of the Directory was necessary and desirable, to be followed by a new communist regime, his secret Insurrectionary Committee belched out one screed after another. It ordered the “extermination” of all opponents, including any foreigners found on the streets. Slogans were adopted for banners proclaiming “the people’s” this or “the people’s” that.

One document that Babeuf likely wrote himself, humbly entitled Analysis of the Doctrine of Babeuf, Tribune of the People, included these statements within its fifteen paragraphs:

“Nature has given to every man an equal right to the enjoyment of all goods.”

“In a true society there ought to be neither rich nor poor.”

“The object of a revolution is to destroy any inequality, and to establish the well-being of all.”

This rabid thrust for equality in all things in economic life always was, and remains today, a destructive and futile assault on human nature. Not even identical twins are truly identical; each of us is a unique assortment of millions of traits and thoughts.

Equality before the law is one thing, and a noble goal, but expecting people to generate identical incomes regardless of their contributions to the marketplace is pure baloney. As I wrote in a chapter on the subject in Excuse Me, Professor: Challenging the Myths of Progressivism:

To produce even a rough measure of economic equality, governments must issue the following orders and back them up with firing squads and prisons: “Don’t excel or work harder than the next guy, don’t come up with any new ideas, don’t take any risks, and don’t do anything differently from what you did yesterday.” In other words, don’t be human.

Utopian Communism

Another of the Babeuf committee’s decrees, bearing the title Equality, Liberty, Universal Well-being, contained a litany of pipe-dreams and the coercion necessary to put them into effect. I excerpt from it liberally here:

“A great national community of goods shall be established by the republic.”

“The right of inheritance is abolished; all property at present belonging to private persons on their death falls to the national community of goods.”

“Every French citizen, without distinction of sex, who shall surrender all his possessions in the country, and who devotes his person and work of which he is capable in the country, is a member of the great national community.”

“The property belonging to the national community shall be exploited in common by all its healthy members.”

“The transfers of workers from one community to another will be carried out by the central authority, on the basis of its knowledge of the capacities and needs of the community.”

“The central community shall hold…those persons, of either sex, to compulsory labor whose deficient sense of citizenship, or whose laziness, luxury, and laxity of conduct, may have afforded injurious example; their fortunes shall accrue to the national community of goods.”

“No member of the community may claim more for himself than the law, through the intermediary of the authorities, allows him.”

“In every commune, public meals should be held at stated times, which members of the community shall be required to attend.”

“Every member of the national community who accepts payment or treasures up money shall be punished.”

“All private trade with foreign countries is forbidden; commodities entering the country in this way will be confiscated for the benefit of the national community; those acting to the contrary will be punished.”

“The republic coins no more money.”

“Every individual who is convicted of having offered money to one of its (the national community’s) members shall be severely punished.”

“Neither gold nor silver shall be imported into the republic.”

In its essence, the utopian communism promulgated by Babeuf and his friends would have made Robespierre’s Reign of Terror seem like a frolic in the doggie park. It would compel men and women back to the Stone Age.

Under orders from the Directory, none other than General and future-Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte forcibly dissolved Babeuf’s organization and arrested much of its membership in February 1797. Babeuf went to prison, and his newspaper was permanently shuttered. His short-lived political career lasted less than three years.

Given Babeuf’s role as the ideological and tactical ringleader of the 1796-97 revolt, the verdict in his trial was a foregone conclusion.

At his trial for attempted insurrection, Babeuf chattered like a drunken cockatiel. Using the occasion to spew his communist ideals before judge and jury and as much of the public as might be reached, the atheist Babeuf even allied himself with Jesus Christ, whom he praised for his alleged “hatred of the rich” and his supposed socialist teachings. Of course, Babeuf possessed no better understanding of Jesus’s words than he did of either human nature or basic economics. As I’ve written here, Jesus was neither a hater nor a socialist.

Given Babeuf’s role as the ideological and tactical ringleader of the 1796-97 revolt, the verdict in his trial was a foregone conclusion.

“We demand real equality or death…And we shall have it, this real equality; it matters not at what price!” proclaimed a manifesto Babeuf’s associates had issued in 1795. On May 27, 1797, both were delivered to the 37-year-old Babeuf himself by way of the guillotine.

Equality in Death

In death, Gracchus Babeuf finally achieved his dream of absolute equality—equality with dead people, which is as equal as it gets and which is precisely the point. The equality Babeuf was committed to foisting on others is both unfit and impossible for the living and achievable only when you’re six feet under.

The truly sad part of the story is that Babeuf’s communist/socialist gibberish was born again with Karl Marx 50 years later.

Men and women of conscience must be both vigilant and courageous in the face of these destroyers in our midst.

Animated by the evil scribblings of Babeuf and Marx, power-hungry demagogues would seize power in diverse places, killing and enslaving millions. They include Lenin and Stalin in the Soviet Union, the Maoists in China, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, and fellow travelers in nations from North Korea to Cuba to Venezuela. All are intellectual heirs and disciples of Babeuf and Marx.

Will the world ever put behind it the rantings of these murderous ideologues? Not so long as evil is a force afoot amongst mankind, I fear. So men and women of conscience must be both vigilant and courageous in the face of these destroyers in our midst.

Lawrence W. Reed is President Emeritus and Humphreys Family Senior Fellow at FEE, having served for nearly 11 years as FEE’s president (2008-2019). He is author of the 2020 book, Was Jesus a Socialist? as well as Real Heroes: Incredible True Stories of Courage, Character, and Conviction and Excuse Me, Professor: Challenging the Myths of Progressivism. Follow on LinkedIn and Twitter and Like his public figure page on Facebook. His website is www.lawrencewreed.com.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.