Since early November of last year, Russia has been amassing troops on Ukraine’s eastern border—with some estimates up to 100,000 troops. From both sides accusing each other of threatening regional stability to NATO members frantically drawing up contingency plans, the Donetsk and Luhansk regions—the contested regions composed of Ukrainians, Russians, and self-proclaimed states—are positioned to serve as the bloody battlegrounds for geopolitical status.

But this is not the first time the Donbas, which encompasses both the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, has served as the site of global upheave. I would personally know.

In the summer of 2012, my family and I moved to Moscow. We moved to assist a joint venture project with Russia’s largest oil company in the Kara Sea above the Arctic Circle. My plan was to enjoy my three years attending the Anglo-American School of Moscow and return home with life-changing experiences away from the United States.

The good news is that I returned home with life-changing experiences. The bad news is that I returned home far earlier than my expected three years abroad due to international conflict.

Following the Ukrainian government’s decision to suspend the signing of an association agreement with the European Union—instead wanting closer ties with Russia—in November 2013, the Ukrainian people revolted. The occupation of government buildings eventually forced the removal of then-President Viktor Yanukovych in February 2014.

Aware of the geopolitical significance of a pro-EU Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin used military force to annex Crimea—a strategic peninsula along the Black Sea’s northern coast within Ukraine—in March 2014.

Russia’s aggression, however, only grew. Russia soon advanced military personal and vehicles into the Donetsk Oblast in eastern Ukraine during the late summer and early fall. Many vehicles were Russian trucks dispatched as humanitarian or medical convoys.

I can vividly recall watching, with my mother on the television, dozens of brown trucks with red medical crosses drive on Ukrainian dirt roads. We soon learned that these conveys were not humanitarian—they were full of Russian soldiers. It was only then did I realize the significance of the situation my family was trapped in.

The primary response by the international community was to place sanctions on Russian individuals, businesses, and officials. Not to be outdone, Russia counter-sanctioned American and European individuals and entities. Combined, hundreds of billions of dollars have been lost from sanctions.

Once the back-and-forth of economic sanctions began, my family began to grow increasingly worried. Especially when, in July 2014, the EU and United States imposed sanctions on Russian energy sectors. Most notably, American companies were banned from conducting business with Russian oil and gas drillers—a knockout blow to the joint venture we were involved with.

As I returned home from a late-September flag football match, my parents informed me of our given ultimatum: evacuate and leave Russia within two weeks, for the threat of individual sanctions were too great.

In a single moment, everything I had planned for my eighth-grade year had disappeared. Plans for speech and debate, basketball, baseball, Model United Nations, student council, and band were gone. I would soon leave the best and closest friends I have ever had. I was to have the place where I learned many of life’s important lessons ripped away from me without a proper goodbye.

In early November of 2014, my family and I returned to Houston. Since then, I have kept a close eye on Russian-Ukrainian relations, for I personally understand how political, economic, and military conflict can directly impact families—especially children.

My eyes have come to the following conclusion: The late 2021 and early 2022 events foreshadow conflict like what happened throughout 2014.

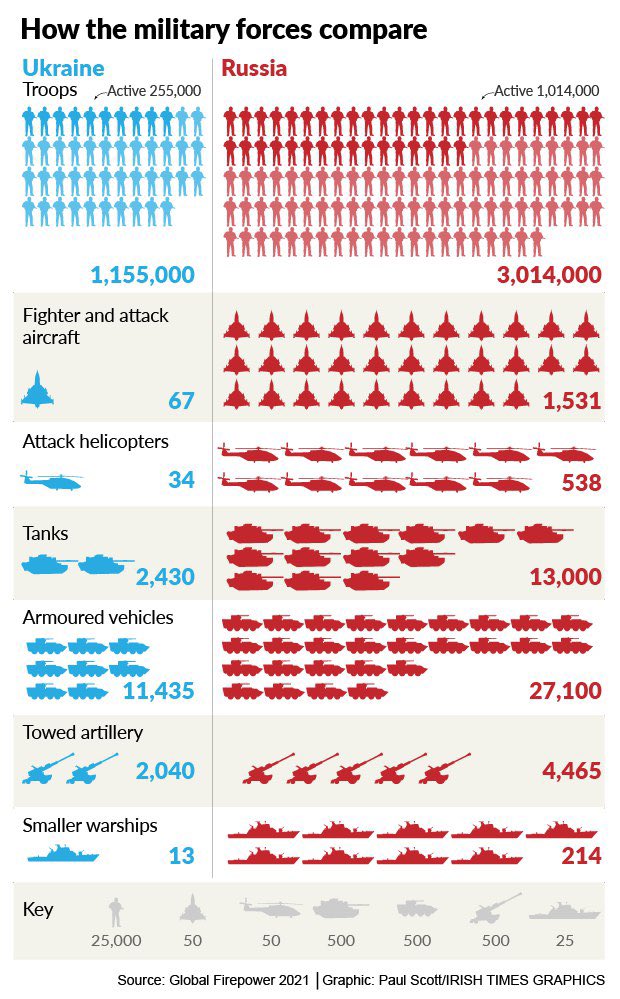

First, Russia is positioning its military to support pro-Russian separatists within Ukraine. With troops, equipment, and logistical services stationed within 300 kilometers along Ukraine’s eastern border, Russia can not only continue its proxy-based support for pro-Russian separatists, but it can quickly move tens of thousands of troops into eastern Ukraine in an offensive manner.

In 2014, Russia’s military quickly moved into Crimea and eventually ordered troops into Ukrainian territory to support pro-Russian separatists. While Russia claims it is simply moving its own troops within its own borders for exercises—which it has the sovereign right to do, the movements do not prevent outsiders from pointing to Russia’s past actions of doing the exact same thing before it sent troops into Ukraine.

Second, NATO members are noncommittal to supplying Ukraine troops. Current member states are reluctant to include Ukraine out of fear of being drawn into conflict with Russia. Since Ukraine is not a NATO member, Article V—the collective security component of NATO—is not triggered.

During the 2014 Russo-Ukrainian War, NATO troops were not positioned in Ukraine to support Ukrainian armed forces. Instead, NATO conducted military exercises within Ukraine and only reinforced member states west of Ukraine. Without direct NATO support, Ukrainian forces were no match for Russian forces and separatists.

Third, Putin is pouncing on a strategic opportunity to prevent Ukraine from growing closer to Europe. Given his requests to rule out further NATO expansion eastward toward Russia’s borders, there is clear incentive for Russia to demonstrate hard power toward a vulnerable adversary that will allow Putin to get his way.

The early 2013 and late 2014 Ukrainian protests triggered a forceful Russian reaction designed to reduce Western influence and take advantage of political turmoil. As previously mentioned, the protests followed the Ukrainian government’s decision to postpone closer ties with the EU in favor of closer ties with Russia. Wanting to keep Ukraine under as strong of Russian influence as possible, Putin pounced on the opportunity to do so.

During my last night in Russia, I walked around my empty house before entering my room—with only a mattress remaining—for the final time. That night, I reflected on my time in Russia. While I wished for a better conclusion on my own terms, I was still able to recall the wonderful times that I still remember to this day.

Regrettably, the potential new Russian offensive against Ukraine brings back the difficult feelings of anxiety, fear, and hopelessness that I felt while watching television with my mother and leaving my friends. The signs for a repeat of 2014 undoubtedly exist.

Instead of brown trucks pretending to be medical convoys, however, it is possible that our televisions will display a convoy of tanks challenging the sovereignty of Ukraine in plain sight.

Andrew J. Harding is a student at The George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and lived in Moscow, Russia, during the 2014 Russo-Ukrainian War.