On Sept. 13, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will release a fresh batch of consumer inflation data for Aug. 2022, what will likely show a drop of the current, annualized 8.5 percent rate as demand contracts in the teeth of another global recession.

In July 2021, inflation grew at a monthly, non-annualized rate of 0.45 percent, and when the new data is released, will fall out of consideration for the annual average inflation rate that gets reported. Put another way, if monthly consumer inflation does not come in at higher than 0.45 percent for Aug. 2022 as oil prices continue to cool from their spring and early summer highs, the 12-month inflation figure will drop from its current 8.5 percent.

The softening in prices comes despite interest rates being kept at historically low levels relative to inflation, with 10-year treasuries coming in at about 3.28 percent as of this writing. The Federal Reserve’s own policy position has put the Federal Funds Rate at about 2.3 percent. Both are well below the nominal rate of inflation.

Interest owed on debt, particularly that charged by the central bank is a means of mopping up excess money out of the economy. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, faced with double-digit inflation, Paul Volcker and the Federal Reserve took interest rates up to double-digit levels. The additional charge for credit had a massive impact on the economy — a large recession intervened in 1982 — but is generally credited with getting the inflation under control.

In this case, under the leadership of Fed Chair Jerome Powell, no such assistance will be provided. The central bank might hike interest rates again at its next Sept. 20-21 meeting, but it will undoubtedly still be well below the rate of inflation, perhaps another quarter or half a percentage point more from its current level.

The worry has to be that hiking interest rates up to address inflation would throw the economy into an even deeper recession.

Leaving the recession as the only force that will be able to tame prices. In fact, the process has already begun, and in the coming months, as prices cool, labor markets will react accordingly, perhaps not until after the Congressional midterms elections in November but certainly as the recession also takes hold in Europe, where energy prices particularly are much, much higher, especially for natural gas-fueled home heating and electricity.

However, owing to labor shortages amid the Baby Boomer retirement wave, there is some thought — or wishful thinking — that unemployment will not be as big a problem in this recession as the last three recessions.

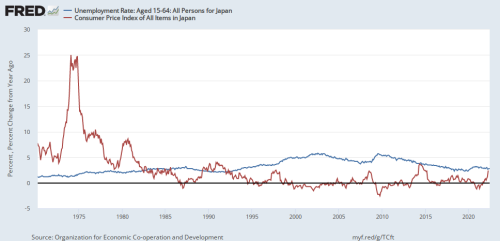

In Japan, in the 1990s, when its aging demographics came into play — birth rates in Japan since widespread use of birth control began in the 1960s have been much lower than even in the West — would set off twenty years of almost no nominal economic growth, coupled with deflation, and a general rising of the unemployment level.

In 1991, unemployment in Japan was at an historic low of 2.1 percent, but as prices contracted, unemployment kept rising, peaking in Dec. 2001 at 5.7 percent. And that was with a retirement wave underway as the workforce aged substantially.

Perhaps that doesn’t seem too high, and in comparison to the Covid recession of 2020 and the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, and their massive impacts on labor markets, with 25 million and 8 million jobs lost, respectively, that’s true. Up to that point, Japan had accumulated massive market share with its export economy that had fed the boom of the 1980s, but alas, its economy could not expand any further, hence the crash.

So, what could that mean for the U.S? With unemployment coming off of historic lows of about 3.5 percent, coupled with still 11 million job openings, barring other intervening factors like another pandemic further economic lockdowns or a massive financial crisis (say, tail risk from European banking arising from the energy hyperinflation), perhaps the current recession won’t be as bad as the last two. One can hope.

The real question is whether the recession will be enough on its own to cool off inflation before the economy starts overheating again. And since the Fed does not appear willing to take interest rates up to the level of consumer inflation, or even the growth of the money supply, still up 5 percent from 12 months ago, we’re about to find out. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation. Reproduced with permission. Original here.