The (International) Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet, commonly known as the NATOphonetic alphabet, is the most widely used set of clear code words for communicating the letters of the Roman alphabet. Technically a radiotelephonic spelling alphabet, it goes by various names, including NATO spelling alphabet, ICAO phonetic alphabet and ICAO spelling alphabet. The ITU phonetic alphabet and figure code is a rarely used variant that differs in the code words for digits.

To create the code, a series of international agencies assigned 26 code words acrophonically to the letters of the Roman alphabet, with the intention of the letters and numbers being easily distinguishable from one another over radio and telephone, regardless of language barriers and connection quality. The specific code words varied, as some seemingly distinct words were found to be ineffective in real-life conditions. In 1956, NATO modified the then-current set of code words used by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); this modification then became the international standard when it was accepted by ICAO that year and by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) a few years later. The words were chosen to be accessible to speakers of English, French and Spanish.

Although spelling alphabets are commonly called “phonetic alphabets”, they should not be confused with phonetic transcription systems such as the International Phonetic Alphabet.

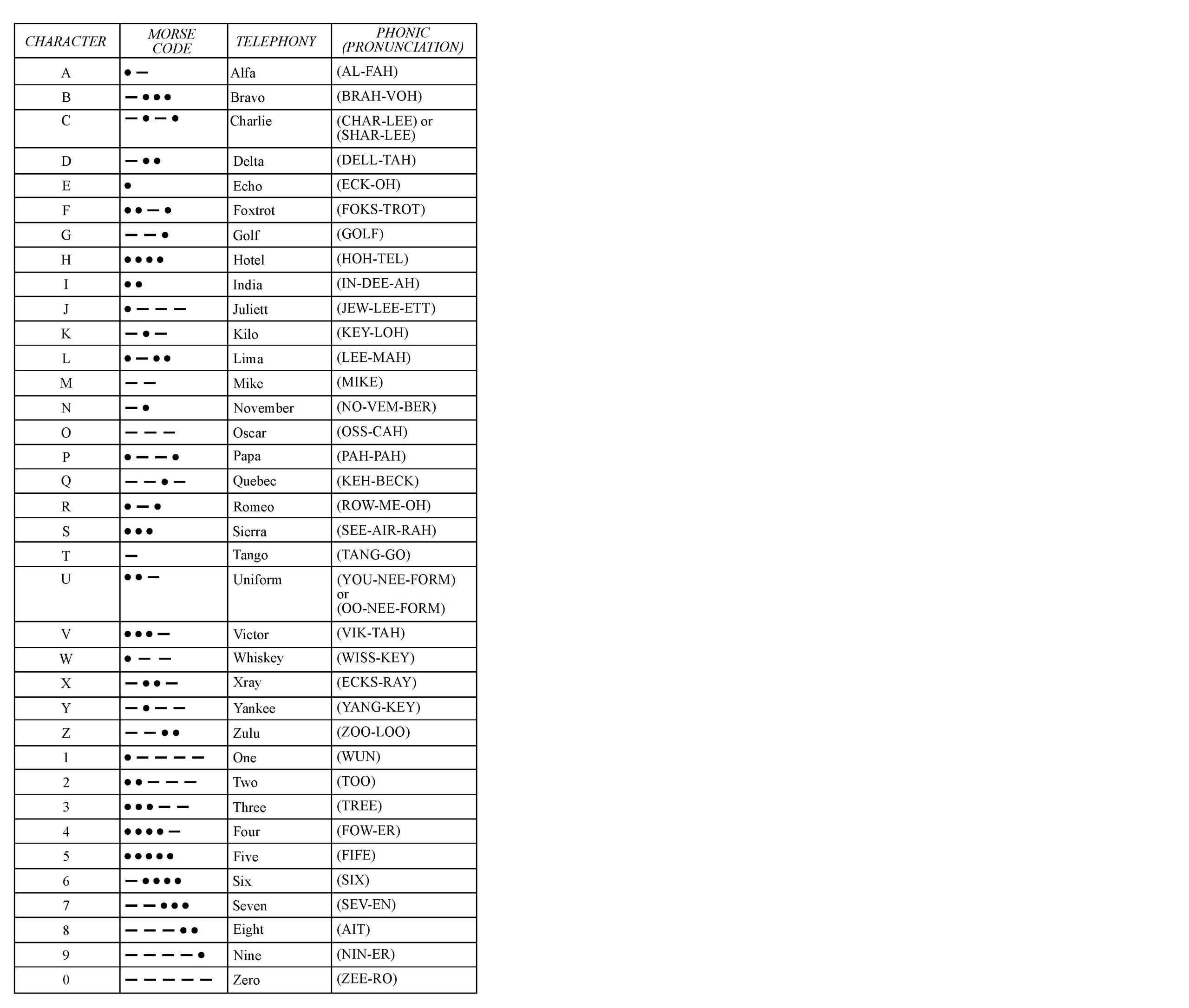

The 26 code words are as follows (ICAO spellings): Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf, Hotel, India, Juliett, Kilo, Lima, Mike, November, Oscar, Papa, Quebec, Romeo, Sierra, Tango, Uniform, Victor, Whiskey, X-ray, Yankee, Zulu. “Alfa” and “Juliett” are intentionally spelled as such to avoid mispronunciation; NATO would do the same with “Xray”. Numbers are spoken as English digits, but with the pronunciations of three, four, five, nine, and thousand modified.

The code words have been stable since 1956. A 1955 NATO memo stated that:

It is known that [the spelling alphabet] has been prepared only after the most exhaustive tests on a scientific basis by several nations. One of the firmest conclusions reached was that it was not practical to make an isolated change to clear confusion between one pair of letters. To change one word involves reconsideration of the whole alphabet to ensure that the change proposed to clear one confusion does not itself introduce others.