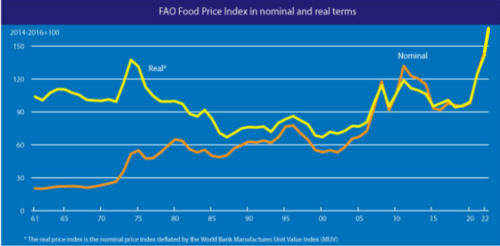

The latest index of world food prices was released by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) on April 8th. The FAO’s Food Price Index climbed to 159.3 in March, which in real terms is roughly double its level in 2000, about 80% above its 2019 level, and the highest since records began in 1961.

Factories closed and workforces were told to stay home even when they weren’t sick. Shipping costs increased because of arbitrary port closures that diverted containers and ships to the wrong places, so exporters struggled to find containers and when they did they couldn’t find ships to put them in. Food rotted in warehouses.

Then came the war in Ukraine, pushing the food situation into even more acute crisis mode.

While the world has plenty of spare food-growing capacity, it takes a few years for additional production to materialize. Existing farms can only slowly increase productivity or bring more land into cultivation. It only takes a month without food for a person to starve to death though, so a two-year food crisis means human catastrophe.

Some propagandists will point the finger at China, which is believed to have huge stockpiles of rice, maize and wheat – perhaps more than half the world’s reserves. Yet it has had those reserves for almost 10 years now. The Chinese have not suddenly bought up food since March 2020 in order to cause wars elsewhere.

How much political unrest is coming our way as a result of the global food shortage? A 2015 paper on the riots caused by food price spikes in 2007-2008 and 2010-2011 found that about two serious riots per month occurred when food prices rose 50% above previous levels. Four to six riots occurred when prices doubled.

Food price levels in early 2022 were already a full 30% above the post-GFC peak, while real GDP per capita for poor countries (see here, for example) was about the same as in 2008 but with much greater inequality. This combination is the core reason why Oxfam in its paper of April 12, entitled “First crisis, then catastrophe”, calculated that close to a billion people in 2022 will be in extreme poverty, facing hunger.

With food prices now a third higher than those that helped spawn the 2011 Arab Spring, we are already seeing food used as a political weapon in Ethiopia, Yemen, and elsewhere. We will undoubtedly see this much more in 2022. Places like Afghanistan and the poorer parts of Africa may well explode politically, as the Famine Early Warning Systems Network is documenting.

Rich Western governments have historically been associated with high levels of social stability and low levels of violence. Are they willing and able to use their riches to contain the consequences of the post-covid famines? Or are they going to be too preoccupied with their own financial problems, wrought by their ailing tax systems and two years of throwing money at misguided covid containment efforts?

The answer is disconcerting, to say the least.

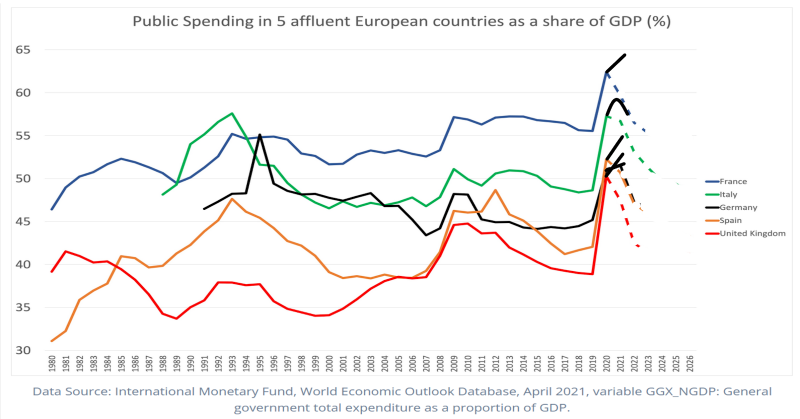

The graph below tracks government spending in five major European countries up to and including 2020. The dashed lines after 2020 show what governments said they expected to happen, while the solid lines approximate what has actually happened, through the end of 2021.

During this period, government revenue has hardly moved, so the extra spending came from more government debt. Debt-to-GDP ratios are rising by about 10 GDP percentage points annually in the EU and the US, more quickly in some places (France, Anglo countries) than others (Scandinavia).

Instead of the predicted decline in government spending after the 2020 rise, the continued escalation of spending in 2021 was spectacular in some countries, such as the UK, France, and Spain. These increases were partly driven by spending on defense and social programs (pork barrelling in advance of important elections in France and Spain), but more particularly by the ongoing covid circus that has led to unproductive spending on all the usual paraphernalia (vaccines, masks, tests) and on the bloated control apparatus that is hanging on to its budget for dear life.

Government spending is higher now than ever before for most of these countries. It is at levels long deemed unsustainable. If you doubt this, consider that the Reagan/Thatcher privatisation reforms of the 1980s and 1990s were preceded by government spending peaks of “only” 50% of GDP.

The tax base problem

Governments have been spending more than they are able to tax. Economists would say that we are now on the right-hand side of the Laffer curve, meaning that attempts to tax more will induce so much tax avoidance that tax revenue will fall. The logic is easy to see in the extreme case: if you tax an activity at 100%, then that activity stops and you get $0 in tax take.

When he was once asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton said “because that’s where the money is.” The problem for government tax collectors today is that, unlike Sutton, they can’t get near enough to where the money is.

Still reading? Click through for the entire article at Brownstone Institute.

The World Catastrophe Wrought by Covid Lockdowns ⋆ Brownstone Institute https://t.co/JvqRFopthz

— Te toroa ???? (@tetoroa) April 21, 2022